The Visigoths' Imperial Ambitions

How an unlikely Visigothic city rose in Spain amid the chaotic aftermath of Rome’s final collapse

March/April 2021

These ruins of a church were once part of the huge palatine complex in Reccopolis, a rare urban settlement founded by the Visigoths in Spain.

Most historians and archaeologists agree: The sixth century A.D. was not an easy time to be alive. The Western Roman Empire had collapsed in the previous century, plunging much of the continent into economic, political, and social upheaval. On top of this, the first outbreak and frequent recurrence of bubonic plague resulted in the estimated deaths of millions. Making matters even worse, a series of volcanic eruptions caused climatic changes from Britain to China, ushering in a cooling period known as the Late Antique Little Ice Age. Recent studies have indicated that this caused drought, crop failure, breakdown in food supply chains, and famine. Harvard University medieval historian Michael McCormick has gone so far as to characterize the period following a particularly intense volcanic eruption in A.D. 536 as one of the single worst eras in recorded human history.

One consequence of this turmoil was that, across most of Europe, many urban centers deteriorated, a process that had begun a few centuries earlier when the Roman state first started to weaken. Cities and towns, once hallmarks of the Roman world and essential instruments of the Roman administrative system, were increasingly abandoned. Masses fled to the countryside seeking survival. Western civilization was irrevocably transformed.

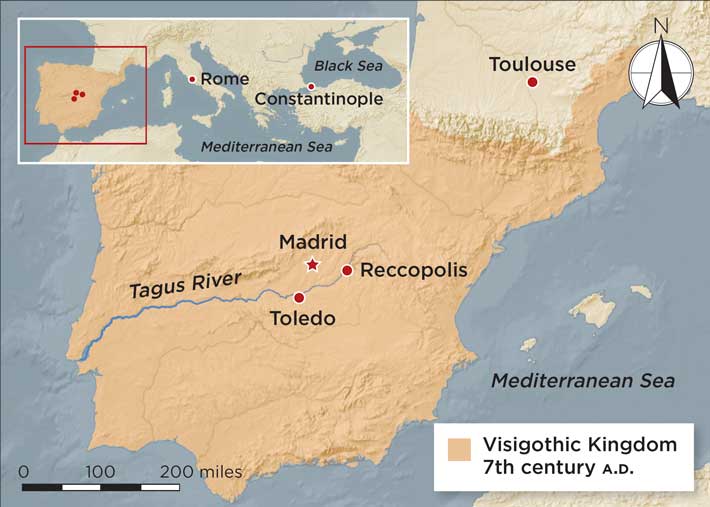

However, recent archaeological work in Iberia, on the periphery of the former Roman Empire, conveys a different story. It is revealing how, against this backdrop of chaos, a people emerged who succeeded in founding perhaps the strongest kingdom in the post-Roman world. These were the Visigoths, who had first arrived in Iberia in the A.D. 410s, when Roman rule was crumbling. Over the next two centuries the Visigoths unified a politically fractured landscape, bringing a semblance of stability to a region racked by centuries of violence and uncertainty. They implemented new taxation and legal systems and reestablished trade with the broader Mediterranean world. The Visigoths also did the seemingly impossible—in a largely deurbanized world, they began to build cities. Written sources suggest that the Visigoths founded at least four new urban centers, but only one of them, Reccopolis, can be identified with certainty. It was one of the crowning achievements of King Leovigild (r. A.D. 568–586), perhaps the Visigoths’ greatest ruler. Today, Reccopolis is an unlikely example of a post-Roman urban settlement that arose amid the disorder and uncertainty of sixth-century Europe. “One does not see many new towns founded during this period elsewhere in the Mediterranean,” says McCormick. “It is quite surprising.”

A gold coin depicts the Visigothic king Leovigild, who founded Reccopolis in A.D. 578.

The Visigoths' Imperial Ambitions

An aerial view of the excavated ruins of Reccopolis shows the remains of the church, the open courtyard, and the administrative buildings of the palatine complex.

Who the Visigoths were and how they became kings of Iberia is a complicated story, the culmination of a journey that took place over hundreds of years and across thousands of miles. The group of people known today as the Visigoths, along with the culturally similar, but geographically separate Ostrogoths, were descended from the nomadic eastern Germanic Gothic tribes who, by the fourth century, had settled on the outskirts of the Roman Empire in modern-day Romania. In A.D. 376, migrations of Huns from the Eurasian steppes drove the Gothic communities across the Danube River and into Roman territory. Initially, the Romans granted them permission to seek refuge within the empire’s borders, but there was little trust on either side as the two groups had clashed regularly for decades along the Danube.

The Visigoths and Romans were at times allies, and at other times enemies. Inevitably, their tenuous relationship boiled over, leading to the Visigothic sack of Rome itself in A.D. 410, the first time the city had fallen to a foreign army in 800 years. Although by this time Constantinople, the seat of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine Empire, was the empire’s most important city, the Visigothic conquest of the Eternal City was a devastating blow, symbolizing the fragility of Roman rule in Western Europe.

In need of a homeland, the Visigoths soon settled in southern Gaul, in what is now France, and established a capital in modern-day Toulouse. By the early fifth century, they followed other marauding bands of Germanic barbarian tribes, including the Vandals and Suevi, over the Pyrenees into Iberia, where the Romans had almost completely lost control. After Rome’s final fall in A.D. 476, the Iberian Peninsula descended into a political free-for-all. “Historians and archaeologists imagine it as a welter of more or less autonomous, competing, and sometimes conflicting power centers and city-states,” says McCormick.

Out of this power vacuum, the Visigoths emerged to seize control. In the early sixth century, they lost most of their territory in Gaul to the Franks, but they began to expand and strengthen their hold on the former Roman province of Hispania, fighting a constant string of battles against other Germanic tribes, Hispano-Romano independent city-states, and Byzantine Roman armies who had managed to regain territory in southern Spain. By the final decades of the century, Visigothic forces, led by Leovigild, had proved themselves the dominant regional power. The king now needed a grand gesture to legitimize himself as the sole ruler of a unified Iberia. He also needed a reorganized administrative system to maintain authority over his now-vast territory. Like the Romans before him, he needed cities. So, like the Romans, he dared to build one.

One Visigothic chronicler, John of Biclaro, records that

Leovigild founded Reccopolis in A.D. 578 and furnished it with “splendid buildings.” Today, the remains of these buildings sit atop a plateau that rises above the banks of the Tagus River in the central Spanish province of Guadalajara. Although Reccopolis is less than a two-hour drive from Madrid, parts of this province have in recent years become some of the most desolate in all of Europe due to financial crises and a dearth of economic opportunities for its rural population. However, 1,400 years ago, the opposite process was underway. The establishment of a Visigothic settlement in the region attracted throngs of people who settled within the new town and formed satellite communities in its vicinity.