Tuesday, May 22, 2018

Saturday, May 19, 2018

The Case to Bring Back the Asylum - WSJ

The Case to Bring Back the Asylum - WSJ

The Case to Bring Back the Asylum

A new generation of flexible, varied institutions would help reduce the vast numbers of mentally ill adults in jails and prisons.

Wednesday, May 16, 2018

Why buying a house today is so much harder than in 1950 - Curbed

Why buying a house today is so much harder than in 1950 - Curbed

...It’s hard to comprehend just how large an impact the GI Bill had on the Greatest Generation, not just in the immediate aftermath of the war, but also in the financial future of former servicemen. In 1948, spending as part of the GI Bill consumed 15 percent of the federal budget.

...It’s hard to comprehend just how large an impact the GI Bill had on the Greatest Generation, not just in the immediate aftermath of the war, but also in the financial future of former servicemen. In 1948, spending as part of the GI Bill consumed 15 percent of the federal budget.

The program helped nearly 70 percent of men who turned 21 between 1940 and 1955 access a free college education. In the years immediately after WWII, veterans’ mortgages accounted for more than 40 percent of home loans.

Tuesday, May 15, 2018

Saturday, May 12, 2018

Credit-Driven Train Crash, Part 1

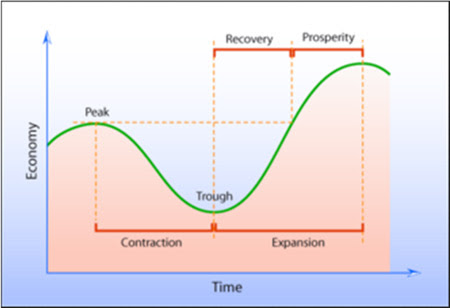

What do we mean by “business cycle,” exactly? Well, it looks something like this:

A growing economy peaks, contracts to a trough (what we call “recession”), recovers to enter prosperity, and hits a higher peak. Then the process repeats. The economy is always in either expansion or contraction.

Economists disagree on the details of all this. Wikipedia has a good overview of the various perspectives, if you want to geek out. The high-level question is why economies must cycle at all. Why can’t we have steady growth all the time? Answers vary. Whatever it is, periodically something derails growth and something else restarts it.

This pattern broke down in the last decade. We had an especially painful contraction followed by an extraordinarily weak expansion. GDP growth should reach 5% in the recovery and prosperity phases, not the 2% we have seen. Peter blames the Federal Reserve’s artificially low interest rates. Here’s how he put it in an April 18 letter to his subscribers.

To me, it is a very simple message being sent. We must understand that we no longer have economic cycles. We have credit cycles that ebb and flow with monetary policy. After all, when the Fed cuts rates to extremes, its only function is to encourage the rest of us to borrow a lot of money and we seem to have been very good at that. Thus, in reverse, when rates are being raised, when liquidity rolls away, it discourages us from taking on more debt. We don’t save enough.

This goes back farther than 2008. The Greenspan Fed pushed rates abnormally low in the late 1990s even though the then-booming economy needed no stimulus. That was in part to provide liquidity to a Y2K-wary public and partly in response to the 1998 market turmoil, but they were slow to withdraw the extra cash. Bernanke was again generous to borrowers in the 2000s, contributing to the housing crisis and Great Recession. We’re now 20 years into training people (and businesses) that running up debt is fun and easy… and they’ve responded.

But over time, debt stops stimulating growth. Over this series, we will see that it takes more debt accumulation for every point of GDP growth, both in the US and elsewhere. Hence, the flat-to-mild “recovery” years. I’ve cited academic literature via my friend Lacy Hunt that debt eventually becomes a drag on growth.

Debt-fueled growth is fun at first but simply pulls forward future spending, which we then miss. Now we’re entering the much more dangerous reversal phase in which the Fed tries to break the debt addiction. We all know that never ends well.

So, Peter’s point is that a Fed-driven credit cycle now supersedes the traditional business cycle. Since debt drives so much GDP growth, its cost (i.e. interest rates) is the main variable defining where we are in the cycle. The Fed controls that cost—or at least tries to—so we all obsess on Fed policy. And rightly so.

Among other effects, debt boosts asset prices. That’s why stocks and real estate have performed so well. But with rates now rising and the Fed unloading assets, those same prices are highly vulnerable. An asset’s value is what someone will pay for it. If financing costs rise and buyers lack cash, the asset price must fall. And fall it will. The consensus at my New York dinner was recession in the last half of 2019. Peter expects it sooner, in Q1 2019.

If that’s right, financial market fireworks aren’t far away.

"It's the best single source of information from many of the investment industry's greatest thinkers." —T.H., Over My Shoulder subscriber |

Corporate Debt Disaster

In an old-style economic cycle, recessions triggered bear markets. Economic contraction slowed consumer spending, corporate earnings fell, and stock prices dropped. That’s not how it works when the credit cycle is in control. Lower asset prices aren’t the result of a recession. They cause the recession. That’s because access to credit drives consumer spending and business investment. Take it away and they decline. Recession follows.

If some of this sounds like the Hyman Minsky financial instability hypothesis I’ve described before, you’re exactly right. Minsky said exuberant firms take on too much debt, which paralyzes them, and then bad things start happening. I think we’re approaching that point.

The last “Minsky Moment” came from subprime mortgages and associated derivatives. Those are getting problematic again, but I think today’s bigger risk is the sheer amount of corporate debt, especially high-yield bonds that will be very hard to liquidate in a crisis.

Corporate debt is now at a level that has not ended well in past cycles. Here’s a chart from Dave Rosenberg:

Source: Gluskin Sheff

The Debt/GDP ratio could go higher still, but I think not much more. Whenever it falls, lenders (including bond fund and ETF investors) will want to sell. Then comes the hard part: to whom?

You see, it’s not just borrowers who’ve become accustomed to easy credit. Many lenders assume they can exit at a moment’s notice. One reason for the Great Recession was so many borrowers had sold short-term commercial paper to buy long-term assets. Things got worse when they couldn’t roll over the debt and some are now doing exactly the same thing again, except in much riskier high-yield debt. We have two related problems here.

- Corporate debt and especially high-yield debt issuance has exploded since 2009.

- Tighter regulations discouraged banks from making markets in corporate and HY debt.

Both are problems but the second is worse. Experts tell me that Dodd-Frank requirements have reduced major bank market-making abilities by around 90%. For now, bond market liquidity is fine because hedge funds and other non-bank lenders have filled the gap. The problem is they are not true market makers. Nothing requires them to hold inventory or buy when you want to sell. That means all the bids can “magically” disappear just when you need them most. These “shadow banks” are not in the business of protecting your assets. They are worried about their own profits and those of their clients.

Gavekal’s Louis Gave wrote a fascinating article on this last week titled, “The Illusion of Liquidity and Its Consequences.” He pulled the numbers on corporate bond ETFs and compared it to the inventory trading desks were holding—a rough measure of liquidity.

(Incidentally, you’ll get that full report on Monday if you subscribe to Over My Shoulder. What you learn could easily pay for your first year.)

Louis found dealer inventory is not remotely enough to accommodate the selling he expects as higher rates bite more.

We now have a corporate bond market that has roughly doubled in size while the willingness and ability of bond dealers to provide liquidity into a stressed market has fallen by more than -80%. At the same time, this market has a brand-new class of investors, who are likely to expect daily liquidity if and when market behavior turns sour. At the very least, it is clear that this is a very different corporate bond market and history-based financial models will most likely be found wanting.

The “new class” of investors he mentions are corporate bond ETF and mutual fund shareholders. These funds have exploded in size (high yield alone is now around $2 trillion) and their design presumes a market with ample liquidity. We barely have such a market right now, and we certainly won’t have one after rates jump another 50–100 basis points.

Worse, I don’t have enough exclamation points to describe the disaster when high-yield funds, often purchased by mom-and-pop investors in a reach for yield, all try to sell at once, and the funds sell anything they can at fire-sale prices to meet redemptions.

In a bear market you sell what you can, not what you want to. We will look at what happens to high-yield funds in bear markets in a later letter. The picture is not pretty.

To make matters worse, many of these lenders are far more leveraged this time. They bought their corporate bonds with borrowed money, confident that low interest rates and defaults would keep risks manageable. In fact, according to S&P Global Market Watch, 77% of corporate bonds that are leveraged are what’s known as “covenant-lite.” We’ll discuss more later in this series, but the short answer is that the borrower doesn’t have to repay by conventional means. Sometimes they can even force the lender to take more debt. In an odd way, some of these “covenant-lite” borrowers can actually “print their own money.”

Somehow, lenders thought it was a good idea to buy those bonds. Maybe that made sense in good times. In bad times? It can precipitate a crisis. As the economy enters recession, many companies will lose their ability to service debt, especially now that the Fed is making it more expensive to roll over—as multiple trillions of dollars will need to do in the next few years. Normally this would be the borrowers’ problem, but covenant-lite lenders took it on themselves.

The macroeconomic effects will spread even more widely. Companies that can’t service their debt have little choice but to shrink. They will do it via layoffs, reducing inventory and investment, or selling assets. All those reduce growth and, if widespread enough, lead to recession.

Let’s look at this data and troubling chart from Bloomberg:

Companies will need to refinance an estimated $4 trillion of bonds over the next five years, about two-thirds of all their outstanding debt, according to Wells Fargo Securities. This has investors concerned because rising rates means it will cost more to pay for unprecedented amounts of borrowing, which could push balance sheets toward a tipping point. And on top of that, many see the economy slowing down at the same time the rollovers are peaking.

“If more of your cash flow is spent into servicing your debt and not trying to grow your company, that could, over time—if enough companies are doing that—lead to economic contraction,” said Zachary Chavis, a portfolio manager at Sage Advisory Services Ltd. in Austin, Texas. “A lot of people are worried that could happen in the next two years.”

The problem is that much of the $2 trillion in bond ETF and mutual funds isn’t owned by long-term investors who hold maturity. When the herd of investors calls up to redeem, there will be no bids for their “bad” bonds. But they’re required to pay redemptions, so they’ll have to sell their “good” bonds. Remaining investors will be stuck with an increasingly poor-quality portfolio, which will drop even faster. Wash, rinse, repeat. Those of us with a little gray hair have seen this before, but I think the coming one is potentially biblical in proportion.

Blowing the Whistle

As you can tell, this is a multifaceted problem. I will dig deeper into the specifics in the coming weeks. The numbers seem unbelievable. I truly think we are headed to a staggering credit crisis.

I began this letter describing the coming events as a train wreck. That comparison came up when my colleague Patrick Watson and I were on the phone this week, planning this series of letters. Patrick and his beautiful wife Grace had just come back from Tennessee, and he told me about visiting the Casey Jones birthplacemuseum in Jackson.

For those who don’t know the story or haven’t heard the songs, Casey Jones was a talented young railroad engineer in the late 1800s. On April 30, 1900, Casey Jones was going at top speed when his train tragically overtook a stopped train that wasn’t supposed to be there.

Traveling at 75 miles per hour, Jones ordered his young fireman to jump, pulled the brakes hard, and blew the train whistle, warning his passengers and the other train. Later investigations found he had slowed it to 35 mph before impact. Everyone on both trains survived… except Casey Jones.

His heroic death made Jones a folk hero to this day. Many songs told the story and even the Grateful Dead and AC/DC paid tribute decades later. (Trivia: He actually tuned his train whistle with six different tubes to make a unique whippoorwill sound. So, when people heard his train whistle, they knew it was Casey Jones.)

Right now, the US economy is kind of like that train: speeding ahead with the Fed only slowly removing the fuel it shouldn’t have loaded in the first place and passengers just hoping to reach our destination on time. Unfortunately, we don’t have a reliable Casey Jones at the throttle. We’re at the mercy of central bankers and politicians who aren’t looking ahead. They can’t simply turn the steering wheel. We are stuck on this track and will go where it takes us.

Next week, we’ll talk about the sequence of how the next debt crisis will arise, how it triggers a recession, and then $2 trillion of deficits in the US and rising debt all over the world. Which just increases pressures on interest rates and lending. And reduces growth. It is not a virtuous cycle.

http://ggc-mauldin-images.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/pdf/TFTF_May_11_2018_3.pdf

Sunday, May 6, 2018

The Great Crack-Up, Then and Now by Sheri Berman - Project Syndicate

The Great Crack-Up, Then and Now by Sheri Berman - Project Syndicate

...WWI was immensely destructive: approximately ten million people died, and perhaps three times as many were injured. By 1918, Europe was shattered, exhausted, and demoralized. And just as the war was ending, a global influenza pandemic struck, eventually killing perhaps 50 million more people.

... By 1918, France was no longer a “power of global rank,” and even the mighty British Empire had been eclipsed by the US. In 1916, US economic output overtook that of Great Britain and its colonies. And by the end of the war, America had emerged with a global pre-eminence “so overwhelming” that many asked if a “universal, world-encompassing empire” might be possible once again...

...WWI was immensely destructive: approximately ten million people died, and perhaps three times as many were injured. By 1918, Europe was shattered, exhausted, and demoralized. And just as the war was ending, a global influenza pandemic struck, eventually killing perhaps 50 million more people.

... By 1918, France was no longer a “power of global rank,” and even the mighty British Empire had been eclipsed by the US. In 1916, US economic output overtook that of Great Britain and its colonies. And by the end of the war, America had emerged with a global pre-eminence “so overwhelming” that many asked if a “universal, world-encompassing empire” might be possible once again...

Wednesday, May 2, 2018

The Cosmic Importance of the Graphene Nano-Tweezers | Mauldin Economics

The Cosmic Importance of the Graphene Nano-Tweezers | Mauldin Economics

...

...

April 30, 2018 The Cosmic Importance of the Graphene Nano-TweezersDear Reader, How do you determine the essence or truth of a thing? Philosophers have argued about the answer to that question for millennia. I’m not going to address this philosophical issue, but I can tell you how scientists are giving us the power to know exactly what any physical thing really is. First, let’s think about why you should care what things really are. Whether you know it or not, it’s almost guaranteed that you’ve been defrauded before because you didn’t know exactly what you were buying. Investigators have shown that high-end computer chips, cotton, clothing, olive oil, handbags, and other products are often swapped for cheap or adulterated replacements by counterfeiters. While these sorts of inferior-quality fakes are irritating, some counterfeits do more than defraud. They endanger lives. Many counterfeiters target products that are components of larger objects. For example, critical airplane parts require expensive engineering, materials, and manufacturing processes. It’s difficult if not impossible to separate the real deal from the clever counterfeit without laboratory testing, so substandard components can make their way into aircraft. We don’t know how many people have died from counterfeit part failures, but experts estimate that more than a half million people a year, mostly in the developing world, die because of counterfeit pharmaceuticals. Similarly, bogus fertilizers, insecticides, and herbicides have ruined crops in poor nations where malnutrition and associated diseases already pose serious threats.  An authentic flash memory IC and its counterfeit replica. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/ There are ways to detect these counterfeits, but the tests are expensive and time consuming, requiring a collection of samples that must be sent to qualified laboratories. Counterfeiters, often part of organized crime rings, know how to circumvent procedures designed to stop them. Once a fake product is in the hands of the end consumer, there’s almost no chance that it will be detected… until something goes wrong. Thanks to a combination of transformational technologies, this is changing. I’m watching right now as the ability to perform advanced molecular evaluations of products makes its way into the hands of consumers. The Next Step: PortabilityThe biggest breakthrough in anti-counterfeiting came a few years ago in the form of invisible botanical DNA barcodes. These codes and unhackable biomarkers can be applied to any physical item, from luxury cotton to pills. Already, these markers are ending counterfeiting in multiple industries. Even the Pentagon now requires that critical components in military electronics include these unremovable labels. To verify the authenticity of a marked product, the DNA markers must be sampled and sent to a lab equipped to perform DNA analysis. Managers of supply chains targeted by counterfeiters do this today, but to end counterfeiting completely, the same analytical power to detect fakes would have to be portable, fast, and cheap enough for everyone to use. Scientists have been working for over 30 years to put the power of advanced laboratories into devices small enough to take anywhere. Their goal is to miniaturize the complex chemical processes used by fully equipped laboratories to identify molecules and compounds. Using fabrication methods similar to those used to make computer chips, they’re developing the lab on a chip (LOC) technology, aka biochip technology. These are tiny chip-sized devices capable of identifying specific molecules. Most assumed that their primary use would be in medical applications, including diagnostics and detection of biotoxins.  Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/ LOC developers turned to microfluidics, the science of reducing large chemical processes to the size of a standard computer chip. To some extent, they succeeded. However, LOCs are still not widely used, because it turned out that precise manipulation of microscopic amounts of chemicals such as reagents and buffers is more difficult and expensive than previously thought. Graphene changes all that. Graphene Opens Up New PossibilitiesGraphene was first produced in 2004 by University of Manchester scientists who used simple acetate (Scotch) tape to lift single-molecule thick layers of graphene from graphite pencil markings. Just like diamonds and petroleum, graphene is carbon and considered a semi-metal. Nanotechnologists make graphene using vapor deposition processes common in chip fabrication. A single layer of carbon 1 atoms self-assembles into a hexagonal pattern similar to chicken wire. Though it is the strongest material ever tested, it is also flexible, and a sheet of nearly invisible graphene can be lifted and held in your hand. For chip designers, graphene’s most remarkable property is probably the fact that it conducts electricity a million times more efficiently than the copper used in common electrical wires. This produces chips so sensitive that they can detect the attachment of a single molecule to a target structure. Besides graphene’s electrical properties, the “semi-metal” has another characteristic that lends themselves to the manufacturing of biosensor chips. Due to its hexagonal lattice structure, it is easy to anchor a large variety of molecules to graphene. A recent critical breakthrough in graphene biochip design came out of the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering, which has designed electronic “tweezers” capable of grabbing specific biomolecules from tiny samples of blood, saliva, or urine. In practical terms, that means we may finally see cheap, disposable biochips, smaller than postage stamps, capable of sending data through smartphones to the cloud for near-instantaneous analysis. Already, scientists and entrepreneurs are building prototypes that will put forensic-level laboratory analysis in your hands and phones. The implications are enormous. The End of Counterfeiting and the New Dawn of DiagnosticsNot only could you check the authenticity of any physical item with an identifying biomarker, making supply chain control open and reliable, common diagnostics will become cheaper and faster too. Your doctor could run an entire metabolic panel or blood test for a fraction of the current cost, while performing a routine checkup. If needed, tests could be done multiple times in a single day to test for individual reactions to foods, supplements, or drugs. There are many more applications for graphene biochips, including true precision medicine and supplementation. However, the most immediate impact may be the end of counterfeiting, which currently cuts global GDP by about 3% annually. Last week, I wrote about a report by Germany’s Berlin Institute for Population and Development, which projects that sub-replacement fertility rates will permanently reduce economic growth. There are, in fact, signs that the global economy is cooling. Graphene biosensors equipped with nano-tweezers are not just a cool new technology. They could help overcome the demographic deficit by reducing economic crime and accelerating next-generation healthcare. |

Tuesday, May 1, 2018

Why Can’t China Make Semiconductors? - Bloomberg

Why Can’t China Make Semiconductors? - Bloomberg

... China is currently the world's biggest chip market, but it manufactures only 16 percent of the semiconductors it uses domestically. It imports about $200 billion worth annually -- a value exceeding its oil imports

...Making semiconductors, by contrast, requires billions in up-front capital and can take a decade or more to see a return. In 2016, Intel Corp. alone spent $12.7 billion on R&D. Few if any Chinese companies have that capacity or the experience to make such an investment rationally. And central planners typically resist that kind of risky and far-sighted spending.

... the biggest long-term challenge for China is technology acquisition. Though the government would like to develop an industry from the ground up, its best efforts are still one or two generations behind the U.S.

... China is currently the world's biggest chip market, but it manufactures only 16 percent of the semiconductors it uses domestically. It imports about $200 billion worth annually -- a value exceeding its oil imports

...Making semiconductors, by contrast, requires billions in up-front capital and can take a decade or more to see a return. In 2016, Intel Corp. alone spent $12.7 billion on R&D. Few if any Chinese companies have that capacity or the experience to make such an investment rationally. And central planners typically resist that kind of risky and far-sighted spending.

... the biggest long-term challenge for China is technology acquisition. Though the government would like to develop an industry from the ground up, its best efforts are still one or two generations behind the U.S.

America’s Mortgage Market Is Still Broken - Bloomberg

America’s Mortgage Market Is Still Broken - Bloomberg

...Loosely regulated companies, financed with flighty short-term debt, did much of the riskiest lending. Loan-servicing companies, which processed payments and managed relations with borrowers, lacked the incentives and resources needed to handle delinquencies. Private-label mortgages (which aren’t guaranteed by the government) were packaged into securities with extremely poor mechanisms for deciding who — investors, packagers or lenders — would take responsibility for bad or fraudulent loans.

...Loosely regulated companies, financed with flighty short-term debt, did much of the riskiest lending. Loan-servicing companies, which processed payments and managed relations with borrowers, lacked the incentives and resources needed to handle delinquencies. Private-label mortgages (which aren’t guaranteed by the government) were packaged into securities with extremely poor mechanisms for deciding who — investors, packagers or lenders — would take responsibility for bad or fraudulent loans.

After the crisis, Congress and regulators took action to prevent a repeat. New rules eliminated the worst of the pre-crisis loan products. Higher capital requirements made banks somewhat more resilient. Yet it’s becoming apparent how much the reformers missed.As soon as borrowers started defaulting in significant numbers, chaos broke out. With little cash or capital, non-bank mortgage lenders imploded by the hundreds. Servicers left borrowers in the lurch — some went out of business, while others saw that they could make more money by foreclosing than by modifying loans. The parties involved in securitizations became embroiled in legal battles about who owed what to whom — litigation that goes on to this day.

In recent years, highly regulated institutions such as Bank of America — burned by billions of dollars in fines — have shied away from the mortgage business. Instead, they provide short-term credit to nonbanks such as Quicken Loans and PennyMac, which do the actual lending. Nonbanks now originate some 60 percent of new mortgages.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)