Wages vs. Jobs

(Excerpted from the August 2017 edition of A. Gary Shilling's INSIGHT newsletter)

Real wages have been stagnant in the U.S. and other developed countries for over a decade. As we’ve discussed in numerous past Insights, this has made people “mad as hell” and has resulted in populist uprisings that spawned Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. Extremely aggressive monetary policy that reduced central bank-controlled interest rates to essentially zero did little to revive economic growth since creditworthy borrows already had plenty of money and banks, scared and chastened after the financial crisis, had little desire to lend to the rest.

Just Around the Corner

Yet, the Fed, first and foremost, but other major central banks as well remain convinced that rapid economic growth and surging labor costs are just around the corner, so they better tighten credit now to head off these threats of serious inflation. It appears that credit authorities believe the nation is in a typical 1950s-1960s business cycle and are not taking into account the many significant economic changes in recent decades. A number of these explains why labor markets are perplexing in the context of that earlier era, but quite rational in today’s climate.

Here are six major aspects of the current atmosphere.

1. Globalization. First and foremost is globalization, the shift of manufacturing and other production in the last three decades from developed countries in Europe and North America to developing economies in Asia, where costs are much lower. The resulting collapse in manufacturing employment in the West has been dramatic (Chart 1).

Furthermore, legal, accounting, medical billing and other services are being outsourced abroad, putting downward pressure on jobs and compensation in those sectors as well. A recent survey by Deloitte reveals the rapid rise in respondents’ plans to outsource many functions (Chart 2). As economies grow, a growing share of spending is on services and a declining portion on goods.

Note that with globalization, many U.S. goods prices continue to deflate. Meanwhile, domestic and international downward pressure is being felt on services as diverse as education, health care, retailing and financial service fees and commissions.

2. Ample worldwide men and machines also restrain U.S. wages and prices. Some policymakers fret that the output gap – the percentage of unutilized output in the U.S. economy – is shrinking fast (Chart 3). This is debatable since the economy’s output potential isn’t a fixed number but depends on speed of growth, which influences the economy’s flexibility. It can adapt much better to slow, predictable growth than to an unexpected surge in demand.

Also, capacity is sensitive to wages and prices. Higher pay attracts new workers who otherwise are comfortable drawing welfare, unemployment and disability benefits. By the same token, high selling prices can make otherwise obsolete machinery profitable to utilize.

On numerous tours of economic consulting clients’ factories, we’ve seen decades-old equipment next to state-of-the-art machines. The old machines are normally unprofitable to operate, but become so in times of high demand for their output and leaping prices. The current overall operating rate (Chart 4) remains below the levels that in the past have initiated capital spending surges, but even previous peaks would not indicate full capacity under the right economic circumstances.

More important, in today’s globalized world, supplies of labor and productivity capacity need to be considered on a worldwide basis, but data is woefully lacking, especially in rapidly-expanding developing economies. By all accounts, global supplies are ample and will remain so, barring all-out protectionist wars and tariff walls in advanced countries that could drastically chop imports.

Like Japan before her, China is moving up the scale of manufacturing sophistication while low-end output is shifting to lower-cost venues such as Vietnam, Pakistan, Indonesia and our long-term favorite, India, which is already robust in technological services exports.

With her rising population growth, democratic government, large privately-owned companies, the English language and a legal system inherited from the British, India seems destined to best China in economic growth and power in the long run, as we have discussed in past Insights. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s efforts to reduce widespread corruption, oversized subsidies for the rural poor, and excessive government regulations are all encouraging.

3. U.S. labor surpluses. Back in December 2012, the headline unemployment rate was 7.7% and the Fed stated that the federal funds rate, then in the 0-¼% range, would be “appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6.5%, inflation one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the [policy] Committee’s 2% long run goal and long-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

U-3 is a well-known measure of labor market conditions and that's probably why the Fed picked it, but it's a very poor indicator of labor market slack or tightness. It is the ratio of those actively looking for work to that group plus the people who are employed.

Consequently, the unemployment rate declines if more are employed but it also falls if fewer are looking for jobs. The latter has dominated in recent years, as shown by the big drop in the labor participation rate, the percentage of all Americans over age 16 who are employed or actively seeking jobs (Chart 5). It peaked at 67.3% in early 2000 and fell to 62.4% in September 2015.

As reported in past Insights, our analysis revealed that about 60% of that decline was due to retiring postwar babies. The remaining 40%, however, was composed of those under 35 years old who stayed in school in the hope that more education would improve their job prospects in the weak job atmosphere initiated by the 2007-2009 Great Recession, and those 35-to-64 who gave up looking for work in a tough employment climate.

Furthermore, the labor participation rate earlier was driven up by women entering the job market, but by the early 2000s, they joined men in reducing their involvement. Further postwar baby retirements in future years will cut participation rates even more.

Without the precipitous drop in the labor participation rate, the headline unemployment rate, now at 4.4%, would be in double digits. The Fed, of course, was forced to abandon its 6.5% unemployment rate target for raising interest rates as U-3 fell and pierced that level in April 2014 when it fell to 6.2%. And U-3 continues to be a poor measure of slack in the labor market for several reasons.

Poor Measure

To begin, our analysis shows the growth in the working-age population will provide ample people to fill further available jobs, even if economic growth jumps from the economic recovery average of 2.1% to our forecast 3% to 3.5% – assuming they have the needed skills.

In addition, many of those who dropped out have not disappeared but may well be drawn back to work for expanding job opportunities. Indeed, the labor force of those age 20-to-29 has been growing since 2012 (Chart 6).

At the same time, people over 65 who are employed or actively looking has been rising since the early 1990s. Many seniors remain in good health and prefer active work to vegetating in front of the TV. Others, among them many postwar babies born in the 1946-1964 years, have been notoriously poor savers throughout their lives and need to keep working due to lack of retirement assets.

As a result of these developments on the young and old ends of the age spectrum, the total labor participation rate appears to have bottomed out. From September 2015 to this June, it rose from 62.4% to 62.8%.

Also, keep in mind that, like capacity utilization data, measures of labor market slack on a global basis aren't available. It certainly appears, however, to be ample, and the skills of workers in Asia are rising rapidly, not only in the production of goods but in services as well.

4. Cost-Cutting. The Fed was, no doubt, aware that after the Great Recession, U.S. corporate cost-cutting propelled earnings in lieu of significant unit volume growth and with negative pricing power. Since most business costs, directly or indirectly, are for labor, those actions axed employee compensation’s share of national income while profits’ share leaped (Chart 7).

In the last several years, however, those share movements have reversed. Whether that’s due to exhausting cost-cutting or picking all the low-hanging fruit while waiting for more to ripen remains to be seen, but compensation’s rising share of national income probably has gotten the central bank’s attention.

5. Shift to lower-paid jobs. Another wage-restraining force in this economic recovery is the job-creation emphasis on low-paid U.S. jobs, as we’ve explored in past reports. It’s been in low-paid sectors such as retail trade where many more people have gained jobs since the depths of the Great Recession, while real wages in retailing have risen just 0.9% in total since the beginning of 2007.

Similarly, the 3.0 million rise in hotel clerks, waiters and other leisure & hospitality jobs in this business recovery has far outstripped the 900,000 gain in manufacturing. In June, manufacturing employees were paid $26.51 per hour, 1.72 times the $15.43 per hour earned by leisure and hospitality workers. In addition, manufacturing employees worked 1.56 times as many hours, so their weekly pay, $1,081.61, was 2.69 times the $402.72 paid to the average leisure and hospitality employee. So the effect of differing sector employment growth has been to retard average wages.

The robust demand for low-skilled, low-paid workers is pushing up their wages as is the proliferation of minimum wage increases in many states and cities. But at the same time, pay increases of those in the 90th percentile are slowing (Chart 8). Nevertheless, so far in this expansion, workers in the 90th percentile have received 20% pay increases while those in the bottom 10th percentile have gained 12.5%, not enough to offset inflation.

Even within industrial sectors, wages have been depressed as postwar babies at the top of their pay scales retire and are replaced by lower-paid new recruits. In contrast, during the Great Recession, layoffs were centered in lower-paid people, many of whom were nice to have around in the previous good times, but not necessary when business declined. That elevated average wages.

More recently, however, new hires have come in at the low end of pay raises, depressing average pay. Furthermore, more so than in past recessions, part-time workers have moved to full-time jobs and 80% of them do so at below-median wages, according to a study by the San Francisco Federal Reserve.

This is especially true for those working part-time “for economic reasons,” i.e., those who want to work more hours than they are offered (Chart 9). This, too, pulls down overall median compensation. Also, 79% of those who have gained full-time jobs but were previously not in the labor force got below-median pay. Ditto for 72% of those previously unemployed when they got jobs.

As a result of these pay differences, the Atlanta Fed’s Wage Tracker series, which measures the wages of continuously full-time employees, has recovered more sharply than other earnings series, even the Employment Cost Index that corrects for employment shifts among industries (Chart 10).

This is a phenomenon similar to the ongoing income polarization discussed earlier. In any event, the fact that those with continuing full-time jobs have fared better than the rest doesn’t mitigate the depressing effect of consumer purchasing power on overall slow wage growth.

6. Union membership. With globalization devastating U.S. manufacturing jobs and cost-cutting pressure on those that remained, union membership in the private sector has collapsed from a quarter of the total workforce in 1973 to 6.4% last year.

This has had tremendous depressing effects on wages since private union jobs pay 19% more, on average, than non-union positions in base pay and over 50% more when health care, retirement and other benefits are included.

State and local government employees have enjoyed much higher pay and even more lush benefits than private sector workers. Nevertheless, municipal employee compensation is under fire from the many states and local governments with strained budgets and vastly-underfunded pension plans. At the same time, municipal union membership is slipping.

Quiescent Labor, Aggressive Management

Despite their lack of purchasing power growth, many employees are reluctant to demand higher pay. Memories of joblessness in the Great Recession are still fresh, as is the understanding that those who quit in the hope of getting a higher-paying job will probably end up with lower pay.

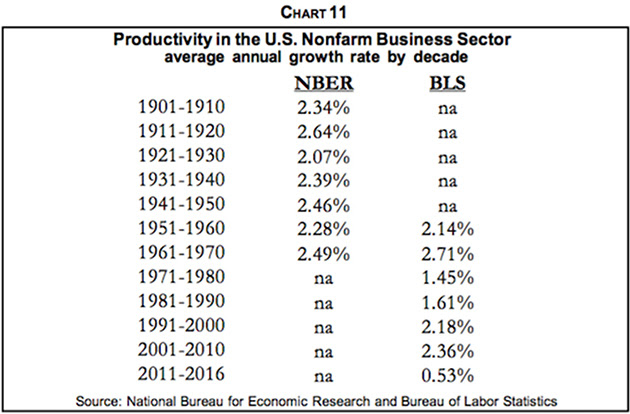

On the other side, most employers, in the face of excruciating foreign and domestic competition, don’t believe they can pass on increased labor costs through selling price hikes. The only alternative is increased productivity, which makes it possible to pay higher wages without cutting into business profits. To put it another way, the value added of any factor of production, including labor, must exceed its costs. And the miserable productivity growth in recent years (Chart 11) has not provided the value added to justify higher wages.

7. Productivity. The definition of productivity is simple. It’s the physical output in relation to all required inputs. It’s the measurement that’s tough. You can measure the widgets stamped out per hour on a punch press, but how do you determine the output of a cell phone?

Furthermore, the number of hours worked is straightforward, but the quality of the work by different employees is problematic. Also, other inputs such as capital, technical expertise and managerial talent are hard to measure. Consequently, the usual but unsatisfactory measure of productivity is output per hour worked.

By this measure, productivity growth averaging 0.53% per year in the 2011-2016 period has been far below the earlier norm of 2% to 2½%. The reasons for the slowdown are unclear, but many possibilities are being discussed that suggest that productivity growth is being significantly understated.

Measurement of Output

Cell phones and other high tech gear probably enhance efficiency of doing business far beyond their cost. Consider the value of time saved by shopping online, which is not captured in the statistics. The costs of new wonder drugs, high as they are, probably do not measure their value in saving lives.

Another explanation for slow U.S. productivity growth as officially reported is that much of it is hidden overseas. In order to avoid paying U.S. taxes, American multinationals have moved intangible assets overseas. Estimates are that between 2004 and 2008, these actions slowed U.S. reported productivity gains by 0.25 percentage points per year.

Delays

We’ve discussed in many past Insights that productivity-soaked new technologies mushroom but often take decades before becoming big enough to raise the overall productivity needle.

The Industrial Revolution began in England and New England in the late 1700s, but only after the 1860-1865 Civil War had it expanded to the point of hyping nationwide productivity. As a result, between 1869 and 1898, real GDP leaped by 4.32% per year (Chart 12) and output per capita leaped at a 2.11% annual rate. In contrast, it’s now rising around 1% annually (Chart 13).

We continue to believe that many of today’s new technologies such as biotech, robotics, cell phones, computers and self-driving vehicles are still in their infancy. In time, however, they should expand to the point that their rapid productivity advances propel overall productivity and economic growth.

That’s a big reason we expect a return to 3% to 3.5% real economic growth in the years ahead, especially as overall demand is driven by fiscal stimuli.

CapEx and Productivity

Many believe that the lack of significant productivity growth in recent years is due to sluggish capital spending, and they attribute that to excessive government regulations, business uncertainty over global developments and lack of clear policies in Washington.

Our research, however, indicates that the greatest driver of plant and equipment spending is operating rates. When they’re high, capacity is strained and more is needed to fulfill orders. When they’re low, as in recent years, there’s little need for more capital spending beyond that aimed at cutting costs and improving efficiency. We found other forces have only small influences on plant and equipment outlays, including corporate profits, cash flow and the growth rates of capacity utilization.

Improved productivity may be embedded in new plant and equipment, but there’s little evidence that big increases in capital expenditures result in surges in productivity. Chart 14 shows the growth rates of the two, and it’s clear that there is little correlation between the change in capital expenditures and the change in productivity. The correlation has an R2 of just 0.8% on a quarter vs. same quarter basis. Leading and lagging data don’t help much later. It shows that a productivity rise now promotes capital spending four quarters later, the reverse of what you’d expect, and that R2 is still a small 31.5%.

Productivity Outlook

Our conclusion is that rapid productivity and, therefore, the wherewithal to increase real wages will revive with the resumption of rapid economic growth in several years, the result of massive fiscal stimuli as well as the maturation of today’s new technologies. Other forces may well push in the same direction.

They include significant tax reform, significant government deregulation (but don't hold your breath; every president since Jimmy Carter has attempted to reduce the financial costs of regulations, but with little success), education reform, unifying licensing requirements, which often vary widely by state, to improve labor mobility and reforming disability, Social Security and other programs that can encourage people not to work.

Also, there’s nothing like a stronger economy to create labor demand and the resulting high employment and wages. As noted earlier, we foresee this in several years as a result of massive fiscal stimuli, spurred by voters “mad as hell” over weak purchasing power for over a decade.

No comments:

Post a Comment