What Could Possibly Go Wrong? |

As you will doubtless have been informed, world equities are now in a bear market. What happens next?

The most excessive speculation has already been washed out of the system. Those warning of bubbles in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, meme stocks, or the growth tech companies owned by the ARK Innovation ETF certainly seem to have had a point. By last November, meme stocks were so exciting that their own benchmark gauge, the Solactive Roundhill Meme Stock index, was initiated. Since then, that index has dropped 70%. The same is true of ARK and bitcoin — this looks like a wave of speculative excitement that flowed into the same things together, and has now flowed out again:

These investments still matter, and it’s possible that they have further to fall. In the case of bitcoin and the crypto sector, it’s also possible that they are big enough for losses to create systemic effects, as their falls force sales of other assets. But they are not central to the questions that confront us now.

What we need to know is whether further accidents lie in the future. And that to a large extent depends on leverage. When unleveraged investments fall, the people holding them lose some of their wealth. That probably has some effect on spending in the economy, but broadly speaking that’s that. Relatively well-off people who hold investment assets are now relatively less well-off. End of.

When leveraged investments fall, companies and their lenders can go bust. The need to pay off the debt can prompt fire sales elsewhere. So, we have our higher rates, and the financial system is now discounting significantly increased borrowing costs into the future. This should bring inflation down — but the risk is that it will create crises for leveraged investments that cause further damage. So, the question, as ever when weighing the risk of a financial crisis, and doing some violence to the French language, is: “Cherchez le leverage.”

| |

| |

Office Property |

If there is one asset that should come under scrutiny, it is real estate, whose life blood is credit. For a double whammy of higher rates and the lasting effects of the pandemic, look to office property. Remarkably, Bloomberg’s index of US office property real estate investment trusts, or REITs, is slightly lower now than it was 20 years ago, and almost back to the lows it hit during the worst of the pandemic in 2020:

For anyone who has beheld the growth of the Manhattan skyline in recent years, barely even slowed by Covid-19, this is alarming. The travails of Vornado Realty Trust, one of the biggest developers in New York, whose share price is 59.5% below its high from five years ago, suggest the scale of the issue; the fact that a number of developers only narrowly fended off industrial action by building staff earlier this year also indicates the pressure. There is a lot of capacity which was planned on the assumption that demand for office space would continue at pre-pandemic rates. That no longer looks a good premise. The fall in REIT prices shows that the concerns are already covered to an extent in the price, but the impact of a large office property developer defaulting on its loans would be painful.

The issue isn’t restricted to the US. European office property isn’t so overblown, and hasn’t suffered quite so much since the pandemic, but the FTSE indexes for euro zone and UK office REITs, denominated here in euro, show similar problems at work:

Many holders of office property, like endowments and big pension funds, are exactly the entities that can swallow a big loss without causing a systemic cascade. But rising supply of offices, plus falling post-pandemic demand, all funded with lots of leverage, is a combination that needs to be monitored closely.

|

Houses |

That brings us to housing. Rates in the mortgage-backed bond market are surging, as would be expected given the move in Treasuries, while the rates actually offered to US borrowers are even higher. Typical 30-year mortgage rates are now a whisker below 6%, and approaching the pre-crisis high of 2006:

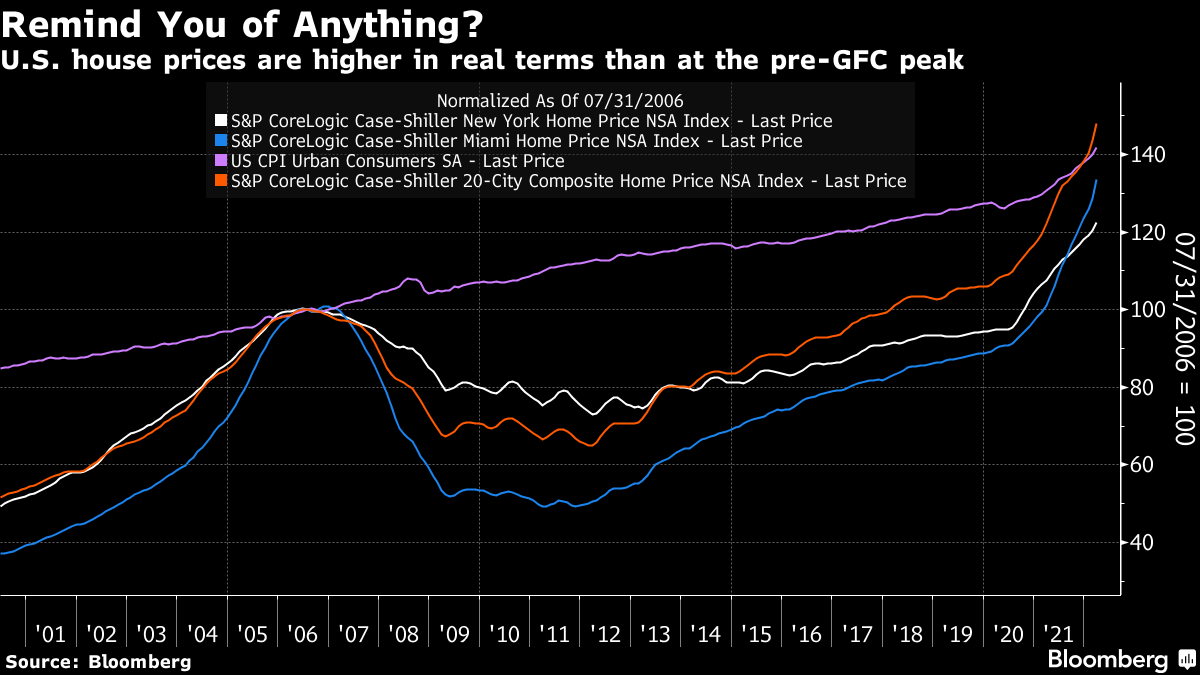

This is another market that has been churned by the pandemic. Demand is shifting. Some locations are no longer so appealing in the WFH era — others are suddenly much more exciting. But the key point is that prices have taken off. The S&P Case-Shiller index of houses in 20 major cities topped in 2006, and had lagged behind inflation ever since — until earlier this year. New York and Miami, which were both the subject of particularly excited action during the property bubble 16 years ago, have also seen prices surge:

This is uncomfortably reminiscent of the conditions that triggered the global financial crisis. Mortgage lending hasn’t been so loose this time, and the main commercial banks aren’t as exposed. So the systemic implications aren’t as profound. But the prospect of suffering leveraged losses on assets that people cannot afford to be without is still painful.

Meanwhile, in the UK, where housing has always been more central to the economy and to animal spirits, there are also reasons for concern. House prices in London, although not the country as a whole, are now higher in real terms than they were at the top of the last boom, according to the Nationwide Building Society house price index. London housing has benefited from the perception that it offers a haven for Russian or Middle Eastern fortunes, so the downward pressure from here could be severe:

Capital Economics Ltd. also points out that new sales instructions to property agents now exceed new expressions of interest by potential buyers. This has been a great leading indicator of falling house prices in the past.

British housing is less exposed to the rates market than it used to be as homebuyers have steadily lost their taste for variable-rate mortgages over the last generation. But if there is one further pocket of speculation in the world that could cause damage when it bursts, it’s British housing, particularly in London.

No comments:

Post a Comment