Extreme heat has engulfed parts of Europe, the US and China. By early last week, at least 86 Chinese cities had issued heat alerts. A so-called heat dome has formed over the Southwest and central US, breaking long-standing temperature records and intensifying what had already been an extremely hot summer. In Europe, the heat wave has been described as the worst in over 200 years, causing wildfires across Spain, Portugal and France. The situation in France and the UK is expected to be particularly intense until Tuesday, with the first-ever “Red Extreme” heat alert issued by Britain’s Met Office.

If you judged by the tabloids, you’d think that a heat wave was fun. Pictures show people sunbathing in the park or relaxing at the beach, and headlines draw comparisons with tropical paradises: “UK warmer than parts of the Maldives.” One 2021 study showed how climate change was almost entirely absent from newspaper coverage of the 2018 heat wave. But this is dangerous — and only going to get worse.

What’s particularly concerning is the rise of dangerous humid-heat temperatures, as explored by David Fickling and Ruth Pollard in this feature. It was thought that the fatal 35 degrees Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit) wet-bulb threshold — the point at which the human body can’t cool itself down and even healthy people with unlimited shade and water will die of heatstroke — almost never occurred in the current climate. But as a 2020 study (and the map below) reveals, humid heat above 35 degrees C has already been happening — from the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea to Pakistan, India, Australia, Venezuela and both Mexican coasts. Wet-bulb temperatures above 31 degrees C have turned up in dozens of places across tropical South and Southeast Asia, China, West Africa, southern Europe, and the Americas, extending to the suburbs of New York and Naples, Italy.

Writing this from an air-conditioned office, it’s easy to forget that there’s no escape from the heat for some. Outdoor workers, for example, are particularly at risk of heat-related illnesses. This map shows how many workdays per year have been unsafe historically due to the combination of temperature and humidity exceeding 100 degrees F.

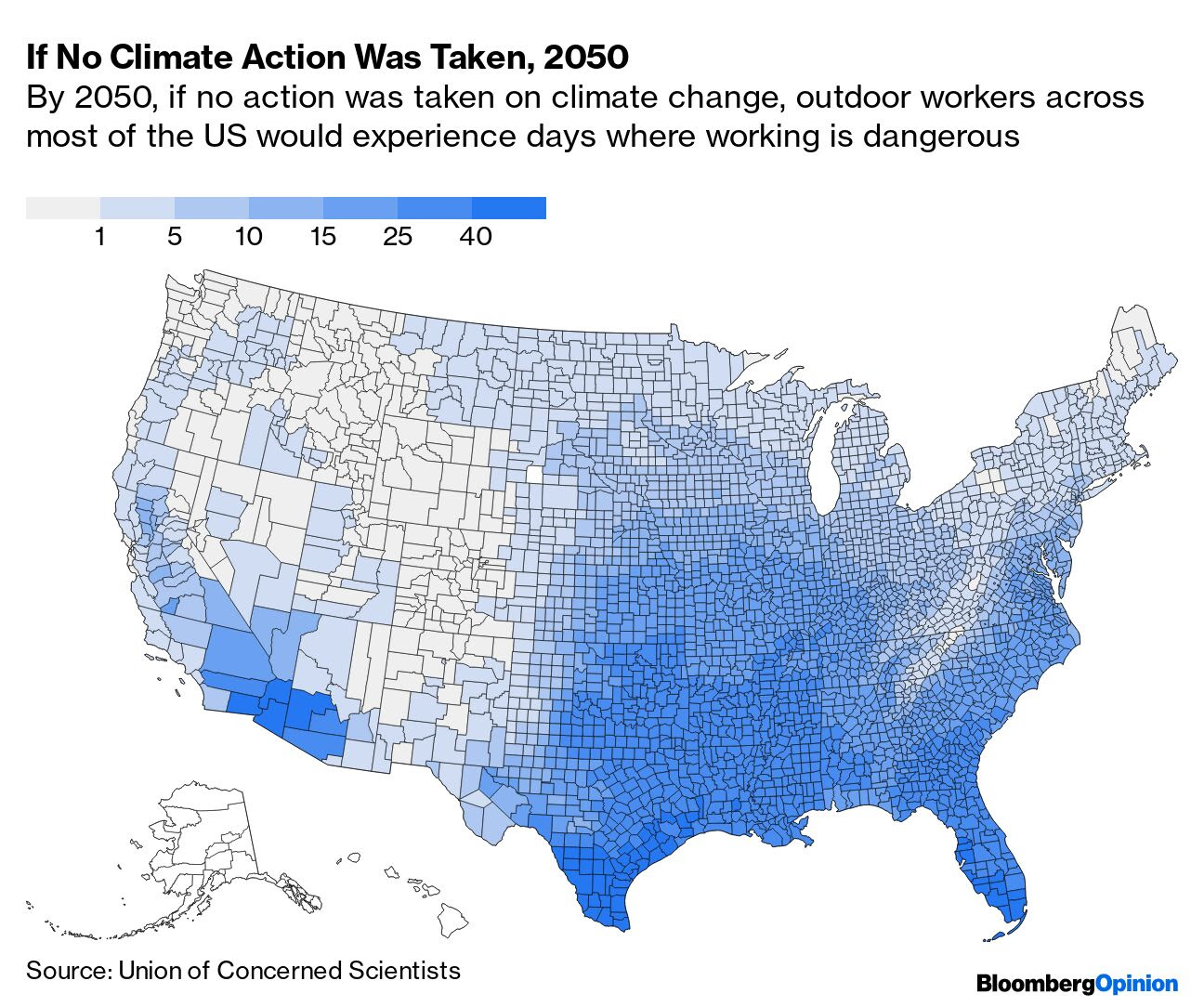

And here’s how many workdays might be at risk, and where, in 2050, if no action was taken on climate change:

Only two states have permanent, enforceable heat-protection standards for outdoor workers: California and Washington. That means most are unprotected, including those in Texas and Florida, where the heat is most extreme.

Meanwhile, in the UK and other typically temperate parts of Europe, even being inside your own home might not be enough to escape dangerously high temperatures. Homes in these regions are designed to keep the heat in during winter and don’t come with air conditioning. In the UK, a fifth of all homes are said to overheat in the summer, meaning indoor temperatures exceed 28 degrees C (82.4 degrees F) more than 1% of the time the space is occupied, or 26 degrees C (78.8 degrees F) in bedrooms.

Europe’s heat wave is making its energy crisis even more critical. As households and businesses turn on their air conditioners, electricity demand has jumped and wholesale power prices have surged. But what’s worse than the heat wave is the little-discussed drought spreading from Germany to Portugal. Javier Blas explains that the lack of rain is making Europe even more reliant on Russian gas by reducing hydropower generation, interrupting the flow of fuel along the Rhine to Germany’s coal-fired power stations and making it harder to cool nuclear plants.

For a visual on the drought, check out the levels on the Rhine right now. During July, it typically flows through the town of Kaub at a depth of about 2.5 meters (8.2 feet). Right now, it’s only 89 centimeters (35 inches) deep.

Extreme heat and drought is also bad news for another essential: food. In India, for example, unusually hot weather in May has caused the nation to cut its wheat production forecast by 6 million metric tons. There is a solution Amanda Little says we should embrace. As the world warms, genetically modified crops — such as a new strain of drought-resistant wheat — are going to be essential to sustainable agriculture’s future.

If you’re enjoying the sunshine this weekend, remember to take the heat seriously. Drink plenty of water, seek shade, wear sunscreen. Some climate activists have suggested that we name our heat waves in a nudge to get people to take proper precautions. Would it work? Stephen Carter is skeptical. We don’t, for example, know much about what naming hurricanes does practically. What we do know is a little concerning: A 2014 paper found that hurricanes with “feminine” names result in greater damage than those with “masculine” names. Why? The authors suggest that those in the storm’s path take fewer precautions because they expect feminine-named storms to be less severe.

More Climate Reading |

No comments:

Post a Comment