Taking Crimea From Putin Has Become ‘Operation Unthinkable’

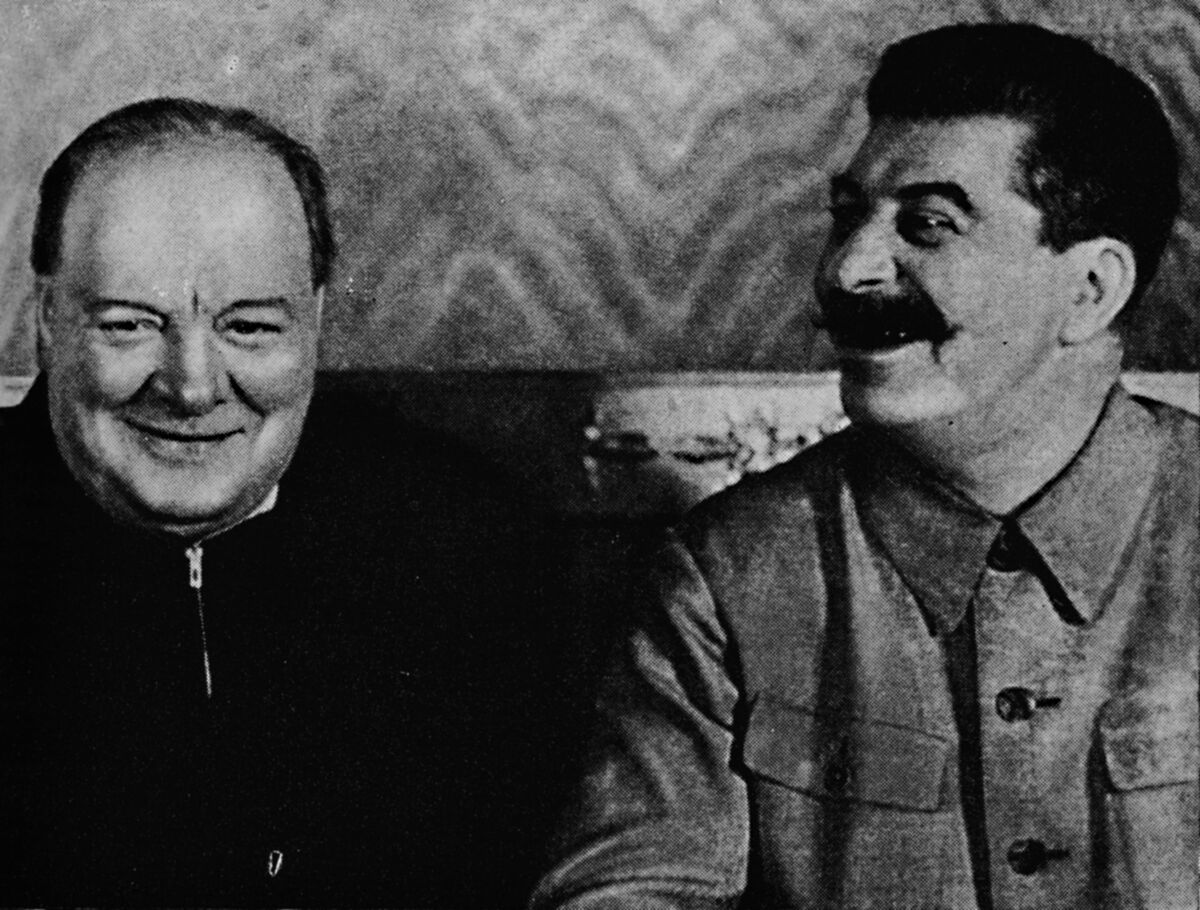

Winston Churchill learned the hard way that dealing militarily with Russians requires some unpalatable trade-offs.

Photographer: Hulton Archive via Getty Images

It is hard to alter facts, reverse realities. This is almost as true in geopolitics as in science. I passionately support Ukraine’s battle for survival against Russian aggression. For almost a year, however, I have been arguing that heedless of where justice lies, and no matter how long the war continues, it remains militarily unlikely that Russian President Vladimir Putin can be dispossessed of Crimea, nor probably of the eastern Donbas region.

Russia can boast centuries of history, and considerable success, as an armed robber — sometimes on a continental scale. The most conspicuous example dates from 1945. By the end of World War II, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was in no doubt that Soviet leader Josef Stalin was a monster, morally indistinguishable from Adolf Hitler.

Most British people, however, together with many Americans, felt a huge gratitude to “Uncle Joe” and the Russian nation for having borne the lion’s share of the human sacrifice needed to destroy Nazism. They lacked sympathy with Churchill’s fury toward Stalin, who was tyrannizing his new empire in Eastern Europe. Britons had grown weary of their elderly prime minister, and especially of his seeming eagerness to seek out new enemies for them to fight now that Hitler was gone.

Churchill had exceptional sentiment, a special anger, about the Poles. In September 1939, Britain and France had declared war on Germany explicitly in response to Hitler’s unprovoked assault on Poland. Yet those allies’ armed forces were pathetically weak. Some prominent British people — not all of them paid-up appeasers — declared that it was grotesque to try to fight Hitler to succor a faraway East European nation that Britain’s army, navy and air force could do nothing immediately to assist.

A clever young Grenadier Guards officer named David Fraser, who later became a general, wrote:

The mental approach of the British to hostilities was distinguished by their prime faults — slackness of mind and wishful thinking … The people of the democracies need to believe that good is opposed to evil — hence the spirit of crusade. All this, with its attempted arousal of moral and ideological passions, tends to work against that cool concept of war as an extension of policy defined by Clausewitz, an exercise with finite, attainable objectives.

In Warsaw, naïve Poles cheered and sang outside the British Embassy, where the ambassador shouted from the balcony: “We shall fight side by side against aggression and injustice!” In truth, the British did nothing of the sort. They reneged on a prewar pledge to launch an immediate bomber offensive against Germany because they were fearful of Nazi retaliation.

The French had likewise promised the Poles that, in the event of war, their army would attack Germany from the west within 13 days of mobilization. In reality, on Sept. 7, 10 French divisions merely advanced five miles into the German Saarland. Then they stopped, and stayed stopped. Was this not rather like Western European nations today, in their less-than-wholehearted support for Ukraine?

By Oct. 5, 1939, the campaign was over. The Germans occupied Poland, which became the only nation in their empire where, in the ensuing five years, there was virtually no collaboration between the conquerors and their subjects. The dirtiest aspect of Hitler’s shameless act of aggression was that the Germans retired into western Poland, relinquishing control of its east to Stalin, in accordance with the secret terms of the August 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact.

Russia ruled the Poles with even more brutality than did the Germans. The fate of the Jews is well known to posterity, but the Nazis and Russians also accounted for the deaths of something approaching a million non-Jewish Poles before “peace” came in 1945.

All these memories were in Churchill’s mind as he raged at the condition of post-Hitler Poland, its people bound with new Russian chains even as Western Europe celebrated its freedom from Nazism. Impulsively, the prime minister seized on the notion that if Stalin continued flagrantly to breach the terms of February 1945’s Yalta Agreement on Poland’s free governance, the West must enforce them at gunpoint. General Sir Alan Brooke, chairman of Britain’s chiefs of staff, was astounded when Churchill demanded to know the prospects of the Anglo-American armies successfully liberating the Poles.

“Winston delighted,” Brooke wrote in his diary on May 13. “He gives me the feeling of already longing for another war! Even if it entailed fighting the Russians!” Ten days later, after further bitter brooding, the prime minister formalized his request. With the “Russian bear sprawled over Europe,” he instructed the chiefs of staff to explore the prospects of challenging the Red Army’s occupation before the British and US armies were demobilized.

He requested the planners to consider means “to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire” to secure “a square deal for Poland.” They were told to assume the support of American and British public opinion (which in truth would never have been forthcoming). Even more implausibly, military leaders were invited to expect that they could “count on the use of German manpower and what remains of German industrial capacity.” The target date for launching such an offensive would be July 1, 1945.

The Foreign Office recoiled in horror from Churchill’s proposal. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, commander of the Soviet occupation zone, wrote later in his memoirs that he had been informed by secret sources that Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, British commander-in-chief in Germany, had been instructed by London to stockpile captured Nazi weapons for prospective use against the Russians.

The Soviets delivered an outraged protest to a subsequent meeting of the Allied Control Commission in Germany. Zhukov wrote: “We stressed that history knew few examples of such perfidy and betrayal of allies’ obligations and duty.” Here was an example, familiar once more in 2022-23, of the Russians’ turning truth on its head, mobilizing their infinite appetite for grievance, even as Soviet firing squads were executing anticommunist Poles by the score.

The British war cabinet’s Joint Planning Staff proceeded to draft a detailed proposal for what was codenamed Operation Unthinkable — a Western Allied offensive against the Russians. I have spent many hours poring over this fascinating 100-page document in our National Archives.

The planners in their preamble were at pains to state that even if the British and Americans advanced east with the sole objective of securing “a square deal for Poland … That does not limit the military commitment. A quick success might induce the Russians to submit to our will … but it might not. That is for the Russians to decide. If they want total war, they are in a position to have it … There is virtually no limit to the distance to which it would be necessary for the Allies to penetrate into Russia in order to render further resistance impossible.

“To achieve the decisive defeat of Russia would require a) the deployment in Europe of a large proportion of the vast resources of the United States b) the re-equipment and re-organization of German manpower and of all the Western European allies.”

The planners conceded that Western air power could be used effectively against Soviet communications, but “Russian industry is so dispersed that it is unlikely to be a profitable air target.”

They proposed that 47 American and British divisions should be committed, 14 of these armored. More than 40 other formations would be retained in reserve, to meet a likely Soviet counteroffensive. The Russians could deploy in response 170 divisions, 30 of them armored: “It is difficult to know to what extent our tactical air superiority and the superior handling of our forces will redress the balance, but the above odds would clearly render the launching of an offensive a hazardous undertaking.”

The word “hazardous” is used eight times to characterize the proposed operation. The war planners warned that communists in Western Europe would seek to sabotage the offensive. While it might be true that the German General Staff would collaborate with the Allies, German soldiers would be unlikely to enthuse about resuming conflict with the Russians.

The British chiefs of staff were never in doubt that the Unthinkable plan was, indeed, unthinkable by anyone save the prime minister. Brooke wrote on May 24: “The idea is of course quite fantastic and the chances of success quite impossible.” In short, Stalin’s Red Army could see off the much smaller US and British forces, even if GIs and Tommies could be persuaded to take up arms against their erstwhile ally.

General Hastings Ismay, the prime minister’s personal chief of staff, told Churchill that the armed forces chiefs would be happy to explain to him why they regarded Unthinkable as impracticable, “but the less put on paper about this the better.” The chiefs did record, however, in a commentary on the draft plan: “Once hostilities began, it would be beyond our power to win a quick but limited success, and we should be committed to a protracted war against heavy odds. These odds, moreover, would become fanciful if the Americans grew weary and indifferent and began to be drawn away by the magnet of the Pacific war.”

It should not be forgotten that this debate in London took place even while the allied struggle against the Japanese continued, notably on Okinawa. Churchill responded to the chiefs of staff on June 10 by admitting that the Russian armies might be capable, if Stalin so decreed, of smashing forward to the Channel coast of Europe. As for Unthinkable, “the Staffs will realize that this remains a precautionary study of what, I hope, is still a purely hypothetical contingency.”

A month later, the Unthinkable file was closed, when the Americans dismissed out of hand the idea of fighting the Russians for Poland or indeed any other Soviet-imprisoned nation in Eastern Europe. President Harry S. Truman cabled from Washington that he saw no grounds for delaying the scheduled Anglo-American withdrawal westward to the occupation zones agreed at Yalta in February.

Stalin got his new empire, and Russia kept this until the collapse of the Soviet Union in the last decade of the 20th century — because the Red Army had got there first. If Churchill or the Western allies had wanted to preserve Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania or the Baltic States from Stalin’s maw, it would have been necessary to stage D-Day in 1943 rather than 1944, and fight a massively costly campaign in northwest Europe a year earlier.

As it was, the Russians had created facts which nobody save Churchill and US General George Patton was willing to dispute at gunpoint. I suggest, with absolute lack of pleasure, that much the same is true today of Putin’s grasp upon Crimea. The only moment at which this could credibly have been challenged was in 2014, when the Russians seized the peninsula and the West largely acquiesced.

All geopolitics demands calculations in which justice, fairness and freedom play only a limited role. A host of people today say: “If the Russians are allowed to keep one hectare of Ukrainian soil, democracy and Western security will be shockingly compromised.” This is true. But just as most of the peoples of the democracies were unwilling to fight a new war for Poland in 1945, so it seems unlikely that they will support a fight to the finish today, to free Crimea. That is ugly, but it is a reality that cannot be reversed.

No comments:

Post a Comment