Venture Capital During the Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1920)

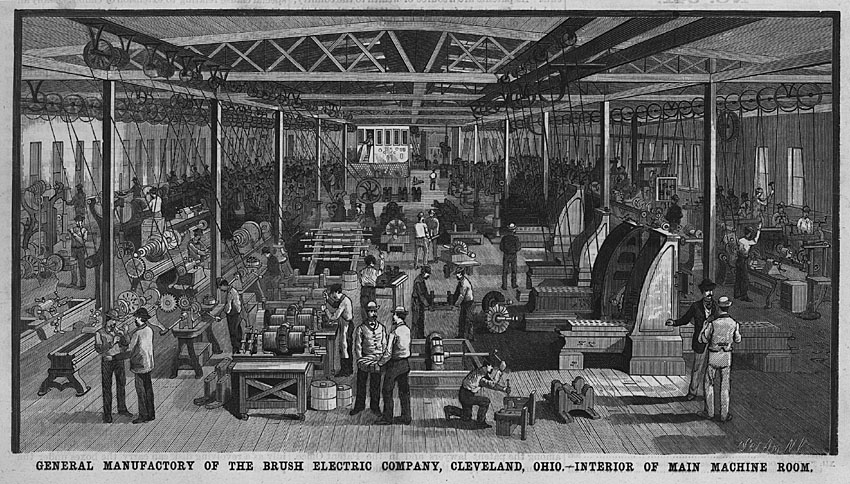

Cleveland’s most iconic innovative company of the era: Brush Electric Company. At one point, Brush manufactured 80% of the nation’s arc lights.

No discussion on the history of IPOs would be complete without covering Venture Capital and the financing of private companies. While today we think of innovation and technological breakthroughs only occurring in coastal cities like San Francisco and New York, this paper looks at the original Silicon Valley: 19th century Cleveland. I’m serious.

“During the Second Industrial Revolution of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Midwestern cities were important centers of innovation. Cleveland, the focus of this study, led in the development of a number of key industries, including electric light and power, steel, petroleum, chemicals, and automobiles, and was a hotbed of high-tech startups, much like Silicon Valley today.

In an era when production and invention were increasingly capital-intensive, technologically creative individuals and firms required greater access to funds than ever before. This paper explores how Cleveland’s leading inventors and technologically innovative firms obtained financing. We find that formal financial institutions, such as banks and securities markets, were of only limited significance. Instead our research highlights the vital role played by a small number of successful local enterprises that both exemplified the wealth-creation possibilities of the new technologies and served as hubs of overlapping networks of inventors and financiers. We conclude by suggesting that such nodal firms have spawned important clusters of innovative enterprises in other places and times as well.”

Cleveland: The Original Silicon Valley

“The continued growth both of local brokerage houses and of trading in local securities resulted in 1900 in the formal organization of the Cleveland Stock Exchange….

As was the case for other exchanges at that time, railroads initially dominated the listings. Compared to the New York Stock Exchange, however, the Cleveland market from the beginning handled the securities of a more diverse set of firms. For example, 52 percent of the firms listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1900 were railroads, and in 1910 the figure was still 48 percent. By contrast, railroads accounted for only 40 percent of the listings on the Cleveland exchange in 1903, and by 1910 the share had fallen to 15 percent. This decline in the relative position of railroads on the CSE owed mainly to the listing of new banks, trust companies and utilities, including several local electric light companies and nine local telephone companies. Between 1910 and 1914, however, the number of manufacturing firms on the CSE more than doubled. The newly listed manufacturers included some of the most successful of the innovative firms formed over the previous several decades (American Multigraph; the Bishop-Babcock-Becker Company; Brown Hoisting Machine; National Carbon; Wellman-Seaver-Morgan, and the White Company).

The important point to underscore, however, is that these firms did not turn to the CSE to raise capital. Nor did their largest shareholders use the market to increase the liquidity of their investments. Trading in the equities of these manufacturing firms was at best light, and it seems that the listings were mainly useful to local brokers who from time to time had small lots of these securities to offer the public. Although venture capitalists today often make their profits by taking firms public and then cashing out their investments, that does not seem to have been the practice in the early twentieth century. To the contrary, investors in start-up enterprises appear to have planned to receive their profits over the long run in the form of dividends on their shareholdings.“

The Brush Electric Company

Source: Global Financial Data

“Looking for a dramatic way to publicize Brush’s invention, Stockly and his associates negotiated a contract with the city of Cleveland to light Monumental Park (now Public Square). Advance publicity brought out a large crowd the evening of April 29, 1879, when Cleveland officials threw a switch, and twelve strategically placed arc lamps flooded the park with light. News of the event spread quickly throughout the country, generating a rush of interest in this new type of street lighting, followed by orders for installations. The successful demonstration also helped the officers of Telegraph Supply line up investors, and the next year the firm was reorganized as the Brush Electric Company with an authorized capital of $3 million, an enormous amount for the time.

Brush Electric installed about eighty percent of the nation’s arc-lighting systems during the early 1880s and made the business people who initially bought its stock rich. As Jacob D. Cox, founder of the Cleveland Twist Drill Company, later regretfully noted: “The original holders made immense sums of money but, as I had no funds to invest, I missed this rare opportunity”. Brush himself became a wealthy man, earning royalties on his patents in excess of $200,000 a year during 1882 and 1883. Indeed, his royalty account accumulated so quickly that the company fell behind on its payments, and to settle the debt, Brush agreed in 1886 to take $500,000 in stock. By the second half of the decade, however, the company was losing ground to new competitors, and Brush, Stockly, and the other major shareholders sold out to the Thomson Houston Electric Company at what appears to have been a handsome price. According to a report in the New York Times, the controlling shareholders (Stockly, Tracy, Leggett, Brush, and Stockly’s sister) owned 30,000 of the company’s 40,000 outstanding shares and sold them for $75 each. The par value of the stock was $50, and its market price was estimated at that time to be $35.”

The Theranos of 19th Century Cleveland

Just like Silicon Valley today, Cleveland had its fair share of enterprising frauds. One particular example is reminiscent of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos attempts to raise money without actually possessing a viable product. The excerpt below describes the electric light industry’s “wild cat” companies that manufactured no products, but still pumped and dump stock with gullible investors by stealing legitimate company’s products and using them in pitches as if they were the company’s. This passage comes from an 1881 issue of the New York Times:

The Role of Financial Institutions

In short, the role of financial institutions was actually very small, even non-existent at times. What is particularly interesting about this historical parallel for Silicon Valley and VCs today is that these original “Venture Capitalists” were more interested in obtaining a return on their investments through long-term growth and dividends as opposed to seeking exits through an IPO or buyout (as is the case today).

“The wealthy Clevelanders who bought shares in these new high-tech enterprises seem to have been motivated by the returns they expected to earn from owning and holding them rather than by the profits they could reap by selling them off after an initial run-up in price. Although a few investors cashed out their investments relatively early (as Lawrence did when he sold off his Brush stock), this practice seems to have been quite uncommon. A search of Cleveland newspapers indicates, for example, that from the time of the formation of the Brush Electric Company until the late 1880s, when the idea of selling or merging the firm was beginning to be discussed, the only mention of Brush shares available on the market occurred around the time Lawrence was selling out. Before the formation of the Cleveland Stock Exchange in 1900, the only firms associated with the Brush hub for which share prices were quoted in the Cleveland papers were Brush Electric itself and the Walker Manufacturing Company. Even after the formation of the exchange, we do not see much trading in the equities of concerns associated with this hub.“

No comments:

Post a Comment