What exact monetary regime are we living in? And how is this all going to end? For that, let us look at the lessons of history.

Inflation Over Time

Financial history is a burgeoning discipline, thankfully. Deutsche Bank AG’s annual long-term asset return study, overseen by Jim Reid, provides some clues as to how changes in the price level behaved over time. As the following remarkable chart shows, inflation as we currently conceive it scarcely existed until the turn of the last century. At that point, it became a global phenomenon:

Obviously, data for earlier centuries can be sketchy. But looking at the median by decade, we see that significant inflation was a rare phenomenon until the 20th century, when it suddenly became the norm:

What exactly changed about a hundred years ago? Here is Reid’s annotated time series since 1210. The establishment of the Fed and the First World War came immediately before the great explosion:

What other things changed at that point?

Demographics

If we are looking for a reason why inflation became much more of a problem in the 20th century, demographic trends looks a plausible candidate. The global population surged in a way never before seen:

Is it possible to discern any longer-term link with inflation? While there must be caveats over such long-term data derived from basic sources, there does seem to be a connection:

What does this portend for the future? As we discussed in the last installment of the book club, the impact of demographics is controversial. Population growth is set to decline in the developed world. But longevity will have an increasing impact. As people live longer, their consumption no longer declines in the last years of life and instead rises sharply, particularly in the U.S.:

Then there is the working-age population. Across the developed world (including China), this is starting to drop both in absolute and relative terms, after decades of increases that were probably a major factor in bringing inflation under control. The entry of China into the global workforce was on this basis possibly the greatest deflationary shock in history.

Now that the number of workers is declining, their bargaining power is rising. Slower increases in the overall population should produce less economic growth and less inflationary pressure. This, though, may be counterbalanced by rising expenditures in old age and pressure for higher wages.

Demographic trends take time to have an impact. But this analysis does suggest that a protracted period in which central banks try to encourage price gains could unwittingly feed into a secular shift to higher inflation before much longer.

Pricing Power

A critical point is whether companies are able to pass on higher costs to consumers. Those that can have what Warren Buffett calls a “wide economic moat” and what others might call a “crushing and probably unfair competitive advantage and a propensity to use it ruthlessly.” Such companies can prosper in conditions of inflation and also, ironically, ensure that it takes hold.

Pricing power was a critical preoccupation of executives and analysts in the latest season of corporate earnings announcements, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s quarterly “Beige Book" of management commentary culled from S&P 500 earnings calls. Company after company, from a range of sectors, complained about rising costs, while many insisted they had the pricing power to avoid a hit to margins.

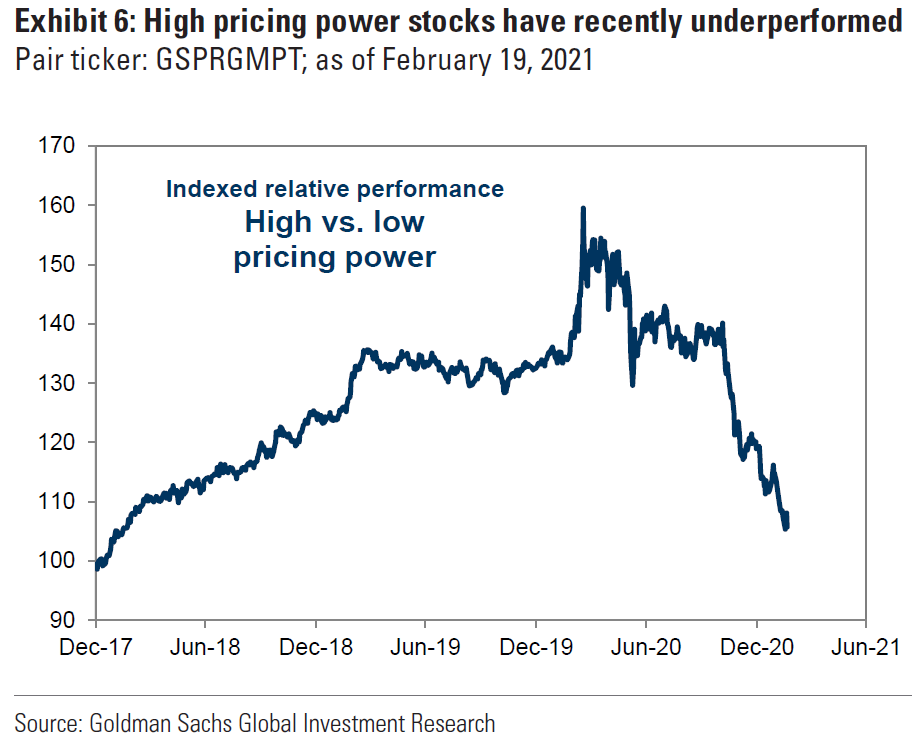

By Goldman’s estimates, the market is less worried than it was. Companies with strong pricing power rallied for several years ahead of the pandemic, and have underperformed badly since then. It might be unwise to expect this to continue if inflation picks up:

This isn’t just a matter of picking stock-market winners and losers. As the following chart from Absolute Strategy Research shows, margins move in line with core inflation. When companies have pricing power, margins thicken and inflation rises. Margins have tightened during the pandemic as companies are forced to maintain fixed costs while revenues drop. Will they surge back?

One of the most trenchant criticisms of contemporary capitalism is that it has become too concentrated, as a result largely of mergers and acquisitions. If concentrated industries are now able to pass on higher prices, inflationary issues grow much more significant — along with the possibility of a political response.

Regime Change

A final question: What kind of a monetary regime are we entering? The elephant in the room for inflation in the 20th century is the abandonment of currencies based on precious metals. Inflation can rise far more easily with a fiat currency, which is reliant on confidence in governments and banks and where the money supply can rise sharply at any time. This can be mightily attractive for governments looking for ways to get rid of debt. Just inflate it away. This is Reid’s central statement after his welter of historical research:

While we still remain in a fiat currency world, the temptation for a great inflationary reset at some point will be ever present. [I]nflation in a fiat currency world is a political choice and very easy to create if there is the appetite and the appropriate policy response. Given the historical precedents, our feeling is that this will eventually be the route many countries will choose to take to reduce their debt burdens.

Changing monetary regimes have repeatedly created new investment regimes since the gold standard ended in the 1970s. This was my attempt to summarize them in a piece for Markets magazine earlier this month:

Broadly, the 1970s saw governments spend heavily once they were rid of the gold standard; that led to inflation and higher oil prices, with equities doing horribly. Then in the early 1980s Paul Volcker persuaded everyone that the Fed would limit inflation. The “Volcker Standard” replaced the old trust in gold until everything got out of hand in the bull market of the late 1990s. There followed the “Greenspan Put,” when the Fed appeared to cut rates whenever asset prices fell. That era climaxed with the global financial crisis and was replaced by the “QE Standard,” where an implicit promise by central banks to keep yields low helped an unsteady recovery. This has been underpinned by an abiding confidence that inflation has been vanquished, and Powell’s words on Tuesday can be seen as an attempt to perpetuate that standard. That would imply continuing rising equity prices relative to gold.

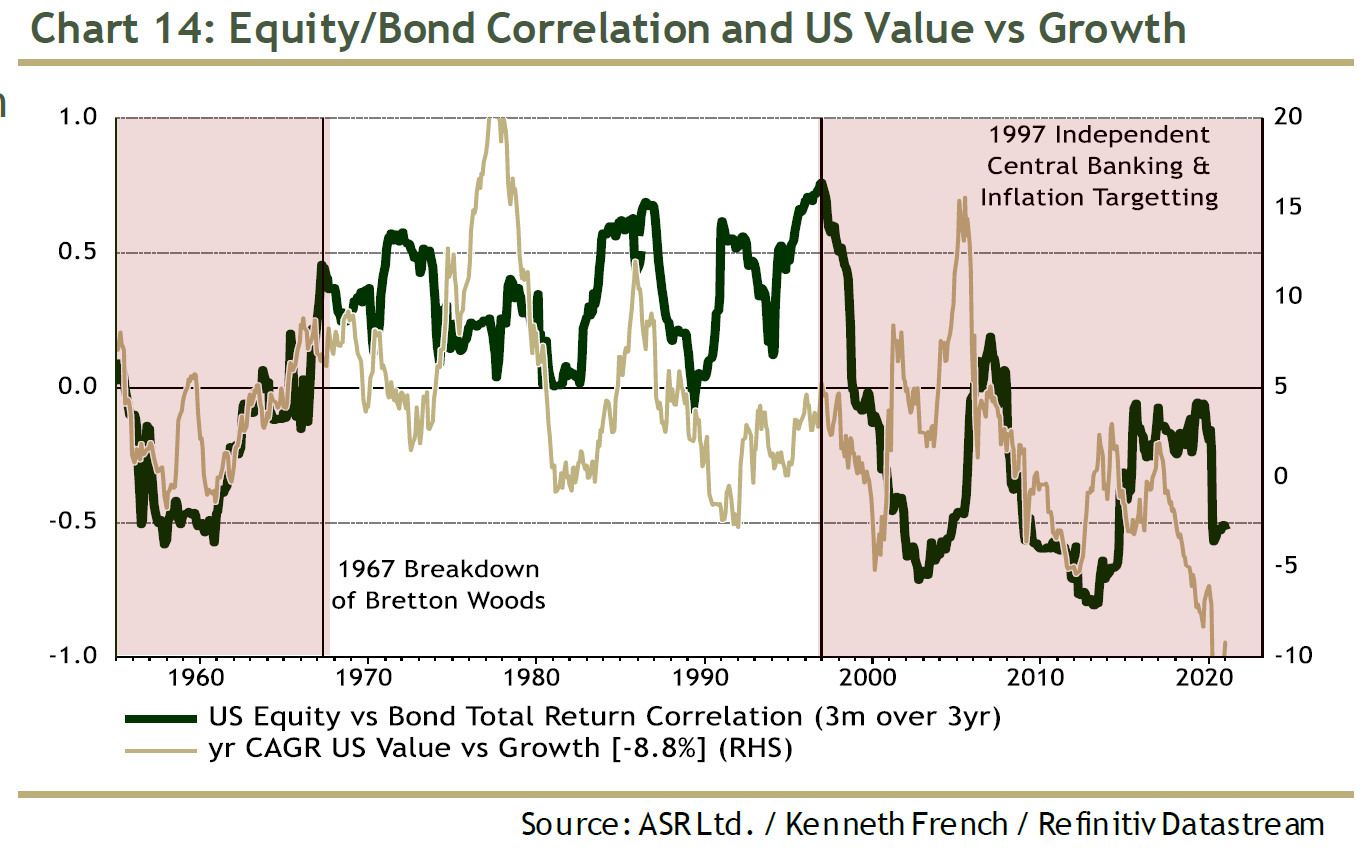

But what if inflation does begin to take off? That would change the investment regime and eventually force a change of Fed policy. For the stock market, Absolute Strategy suggests we might return to something like the so-called Fed Model of the 1990s, when analysts expected earnings yields on stocks and yields on bonds to follow each other:

Does that mean a period similar to the 1970s, when inflation ran amok? Absolute Strategy suggests the 1950s as another analogy. This was also marked by financial repression, as the Fed and other central banks kept a limit on bond yields to ensure people lent money to the government at cheap rates. Absolute Strategy suggests that the 1950s-style experience of loose fiscal policy combined with accommodative monetary policy could spur nominal economic growth and deliver a dynamic rotation into value:

The puzzle will persist. Powell and other central bankers are evidently attempting to prolong the QE Standard. Investors with an eye to the future should ask what will happen if inflation returns. To prepare for such an environment, it would be best to avoid bonds, and to continue piling into the value stocks whose recovery was interrupted by Powell on Tuesday.

No comments:

Post a Comment