Xi’s Big Mistake

July 16, 2021

Selling the Rope

“Prepare for War”

Sleepwalking to Confrontation

China Problems and Big Brother

Washington DC, Maine, and Colorado

I have mixed feelings about China. On the plus side, I think

the country’s massive economic transformation may be one of the most impressive

events in human history. Bringing hundreds of millions from primitive rural

lives into relatively prosperous cities within a few years was awe-inspiring. I

greatly admire the millions of Chinese entrepreneurs worldwide who create jobs

and technology. They’ve helped the entire world in countless ways.

And yet, I can’t forget that China’s leaders are devoted,

ideologically centralist communists. Americans sometimes apply that term

casually to our political opponents. Xi Jinping is an actual communist. His

regime permits some limited market-like activity, but only to help achieve the

government’s goals, which remain communist.

When the West first began engaging with China in the 1980s

and then allowed it into the World Trade Organization in 2001, many hoped

exposure to our ways would tug China toward capitalism. It seemed to be

happening for the first few decades, too. But the hope is fading.

In a 2015 letter

(When China Stopped Acting Chinese), I said this:

Beijing’s stimulus efforts

created the stock market bubble; now their unsuccessful efforts to keep it from

bursting are shaking my confidence in their desire to allow market forces to

play a greater role in the transition from a top-down society to a

consumer-driven, bottom-up society.

Still, I’ve learned not to

underestimate the Chinese leadership. They make mistakes but usually

recognize them and change course quickly. We’ll see what they learn from

their current misadventures in stimulus and their attempts at top-down control

of an essentially uncontrollable market. If they don’t learn the right lessons,

China will face an even harder lesson in the future.

Six years later, it looks like Chinese leaders didn’t learn

the right lessons. Xi has been trying to balance

economic freedom and authoritarian control and it’s not working like it used to.

Today we’ll review some recent events that illustrate where Xi went wrong. Then we’ll

think about whether the Xi government can change course, whether it wants to…

and whether it will survive.

Selling the Rope

Chinese ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing had its US initial “public offering” (I’ll explain

those quote marks in a minute) last month, raising $4.4 billion. The shares

plunged a few days later. Why? Widely called the “Uber of China,” Didi seems to

have good prospects. The problems came from outside.

For one, the Chinese government decided to investigate

whether Didi presented a “cybersecurity threat.” The company was ordered not to

accept new users and its mobile apps were taken down from online app stores.

But audits, or lack thereof, may be a bigger problem, and not just for Didi. My

friend Mark Grant explains in one of his letters this week:

The core of the issue is that the

Chinese government will no longer give US market regulators, any of the

regulating bodies, the power to inspect the audits of Chinese companies listed

on US exchanges. There are at least 248 Chinese companies, listed on three

major US exchanges, with a total market capitalization of $2.1 trillion,

according to the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

Earlier this year the Securities

and Exchange Commission began rolling out rules threatening to delist foreign

companies from American exchanges if they do not meet US auditing standards for

three years. The Chinese response was that Chinese regulators will conduct the audit

inspections and deliver their conclusions to the US Public Company Accounting

Oversight Board. This was soundly rejected, as it should have been, by the

SEC. (emphasis mine)

In the press, recently, there have

been all kinds of talk about the Didi IPO fiasco and the effect on Chinese tech

companies and on new Chinese listings. This is all fine, but it does not go

nearly far enough. The issues are much,

much bigger.

On the equity side, how can you invest in a Chinese company, any Chinese company, regardless of size, or theoretical revenues or profits, without audited financials? There will be no way to know if any of it is accurate and foreign assertations will have all of the reliability of a drop of water purportedly not dripping down the Great Wall, because of the Chinese sunlight. No one will have any reliable knowledge of what is actually going on. No one, in his right mind, would invest in any company, domiciled anywhere, on this basis.

Mark is right; investors shouldn’t throw money at companies

based on financial statements that don’t have some kind of trusted

third-party verification.

But there’s a bigger problem here. The Didi IPO was not a

normal IPO, at least as we think of them in the West. US investors who bought

these “shares” don’t actually own equity. They own pieces of a Caymans

“variable interest entity,” (VIE) which has a contract with the parent company.

This structure is necessary because under Chinese law foreigners can’t own

Chinese shares directly.

Didi duly warned

investors in its US offering (see risk factors in their registration

statement) that they had no shareholder rights and the Chinese government had

final control. This isn’t new. US-listed Chinese companies since at least

Alibaba in 2014 have used the VIE structure. It’s one of those things that

works great until it doesn’t.

This arrangement did have a key advantage, though, at least

for the Chinese. It let Chinese enterprises rake in foreign capital while

giving up no ownership and reserving the right to leave their own “investors”

high and dry. This method may now be approaching its expiration date but it worked

well for a long time.

That’s how Xi and the

Chinese Communist Party operate. They do things that look capitalist but

really aren’t, lacing them with unnoticed poison pills for later use.

It’s similar to their appropriation of US technology, trademarks, and other

intellectual property. We are literally selling them the rope.

“Prepare for War”

We should distinguish

between Chinese business leaders and the Chinese government. I think the

former are mostly just trying to run their companies the right way. They are

like entrepreneurs everywhere, trying to grow their businesses to the best of

their ability. The latter group makes it difficult and sometimes impossible.

This can be hard to grasp. Xi and the other communists

really believe they can have it both ways, conducting “business” while

also maintaining iron-like control over everything. They may not exercise their control, but they

want to have it.

Those VIE companies are a good example. Some experts say the

whole structure is illegal under Chinese law, yet it is widely used. The

government looks the other way. But by doing so, the authorities give

themselves a giant weapon they can use any time. The business executives are

aware of this and modify their behavior accordingly. (Note that verb “modify.”)

In theory, this could still end well. Having successfully

allowed people a taste of capitalism and its benefits, the government might

think it can continue. Meanwhile those capitalist benefits might gradually

usurp the Communist ideology.

Recent events say that’s unlikely, though. Beijing

appears to be concluding it has squeezed all the advantage it can from

capitalism. Is Didi any more a technological risk than scores of other

companies? Not really. Sometimes you have to create object lessons to keep everyone in line.

In hindsight, things seem to have gone wrong after the 2008

financial crisis. Facing potential social unrest, China responded with

massive debt-financed investment in infrastructure, housing, and other

projects. Some were needed, others were make-work distractions. But all the

debt was real. And over time, it has become a heavier burden.

Xi Jinping inherited this situation when he took power in

2013. What is his plan? According to Cai

Xia, a Chinese

professor and high-level CCP member and now expatriate dissident living in the

US, Chinese Communism hasn’t changed. She wrote a lengthy paper under

the auspices of the Hoover Institution. She maintains Xi is merely dropping the

pretense.

Here’s Ambrose

Evans-Prichard in a recent Telegraph column, writing a useful summary.

Like many amateur observers of

China, I had assumed that Xi Jinping’s iron-fist policies at home and abroad

were a break with the more emollient approach from Deng to Hu Jintao (if you

can call the Tiananmen Square massacre emollient), when China seemed to be

softening from a totalitarian to an authoritarian regime. Cai Xia makes clear that the

fundamental character of the CCP has been unchanging.

The party has merely dropped the

facade and dispensed with Deng Xiaoping’s tactical dictum: “bide your time, and

hide your strength” (韬光养晦). It has also acquired the means of totalitarian control

that Hitler and Stalin could only dream of, whether face recognition technology

or digital tracking through the Social Credit System.

The long list of Xi’s affronts,

from the Nine Dash Line to the South China Sea, to the pitiless asphyxiation of

Hong Kong, to the intimidation of Australia, to the Uighur camps, are by now

well-known, culminating in wolf warrior diplomacy and state-sponsored

disinformation on Covid-19.

We are so inured to it that

President Xi’s “wall of steel” speech at the 100th birthday party almost seems

banal. We know what the party thinks. The Fifth Plenum text setting out China’s

strategy until 2035 revives the term “prepare for war” (备战), not used for over half a

century.

“Prepare for War” is an exaggeration, at least I hope, but

it is growing less unthinkable. When you have two great powers whose systems

are irreconcilable, and neither is willing to change, the options list shrinks.

Sleepwalking to

Confrontation

Not everyone thinks disengagement and confrontation is

inevitable. Ian Bremmer outlined the issues in his last letter, reaching a

different conclusion.

Ian pointed out that unlike the US-USSR Cold War, the US and

China are highly interdependent. He broke it down into three components:

Hostility (where both countries want the other

to fail): This includes mostly the national security issues like Taiwan and the

South China Sea, plus issues both countries see as core principles, like

China’s treatment of Hong Kong, the Uighurs, and Tibet.

Competition (each wants to outperform, but not

destroy the other): These are the economic issues, like international trade and

investment, technology, and domestic political stability. Both countries are

the other’s supplier as well as customer. Each wants to win, but also needs the

other.

Cooperation (both want to work together for

mutual gain): This includes the global challenges like climate change,

terrorism, etc. They agree on the goals but lack of trust makes cooperation

difficult.

We naturally focus on the areas of conflict, but Ian

thinks the full US-China relationship is actually working pretty well. It changes with time, of course. Ian rates

the relationship as currently 20% hostility, 70% competition, and 10%

cooperation. But he also says much of the competition is becoming

hostility.

Ian takes as given that neither country will do anything

that would be perceived as “weakness.” But if no one will blink, how do you

avoid coming to blows? Ian thinks it is possible.

More likely, a change in policy comes from internal failures

of the present trajectory. How would that happen?

In China: Xi leans into more state control of strategic

sectors, high-performing talent starts to leave, productivity dives, and growth

stalls and debt spirals… giving technocratic Chinese political leaders more

space to nudge Beijing policymaking back towards more interdependence.

In the United States: Domestic divisions make industrial

policy half-hearted, the private sector retains capture of the regulatory

environment, the post-Biden administration renders strategic reorientation of

the US economy incoherent and affords allies more space to direct their own

course.

Historians tell us the dangers of sleepwalking into

confrontation. But in the US-China relationship, domestic incoherence and lack

of ability to effectively implement long-term strategy makes cold war less

likely… precisely because it allows existing forces of interdependence to

persist unmolested.

I hope Ian is right. From my perch, I’m not sure much of

this is feasible. I think Xi has made a giant mistake with recent business

crackdowns. He may have calculated he

can do without Western companies. But without them, what will happen to

the Chinese businesses that still turn to the US and Europe for capital,

customers, expertise, and technology?

Moreover, can the Chinese miracle continue if millions of

small entrepreneurs stop believing the government will let them succeed? I

don’t mean big companies. I’m talking about restaurant owners, drivers,

shopkeepers—all those who keep the economy moving.

Cai Xia, who was in a position to know, has an even more

chilling outlook.

Cai

Xia’s contention is that the Communist regime is more brittle than it looks, like the Soviet regime before the end.

“I recommend that the US

be fully prepared for the possible sudden disintegration of the [Chinese

Communist Party],” she said.

Imagining what such a “sudden disintegration” would look

like, I suspect it wouldn’t be pretty, even if good in the long run.

Economically, it could make 2008 or even the COVID pandemic look mild.

China Problems and Big Brother

China is facing large problems, some obvious and others more

subtle. But I think problem number one is Xi has made a giant mistake with

recent business crackdowns.

China is the ultimate

Orwellian Big Brother state. Especially within the cities, the government

can literally watch everything you do and track everything you buy, from your

noodles to your clothes, who you talk to, what websites you visit. All of the

data Chinese corporations gather is available to the CCP, who use it to create

China’s “social credit system.” If you Google that, the first thing that pops

up says this:

The China social

credit system is a broad regulatory framework, intended to report on the

“trustworthiness” of individuals, corporations, and governmental entities

across China.

The consequences of a poor social credit score can be

serious. It affects travel prospects, employment, banking access, and ability

to enter contracts. On the other hand, a positive credit score can make a range

of business transactions easier for both individuals and corporations. Foreign

businesses have to work with consultants to make sure they have good social

credit scores, and the CCP dictates what that means. It is the ultimate

top-down centralist panopticon.

As mentioned at the beginning, many Chinese are quite entrepreneurial, given the opportunity. That

being said, entrepreneurialism is not a racial characteristic. There is

something in an entrepreneur that makes them want to start their own business

or enterprise. A willingness to take risk is obviously part of that DNA. The

United States is extraordinarily lucky in that we attracted people who were

willing to take risks simply to come here.

I may not understand the Chinese mindset, but I think I have

a pretty good grasp of the entrepreneurial mindset. Successful entrepreneurs

don’t fit into a mold. You can see why some entrepreneurs thrive and you have to scratch your head to figure

out how others did it. Some work well within their system. Others simply create

new territory and methods.

Xi is going to deprive China of that second set of

entrepreneurs, those willing to create something entirely new that might not

fit well within the current social credit system. I think the growing Big

Brother state will stifle innovation. Who wants to risk their social credit

score? It is one thing to risk your reputation and capital, and another to risk

your ability to live and work.

China’s panopticon

blocks that risk-taking impulse. The consequences will accumulate and

reduce growth. And with over half the country still living in extreme poverty,

that doesn’t bode well for the future.

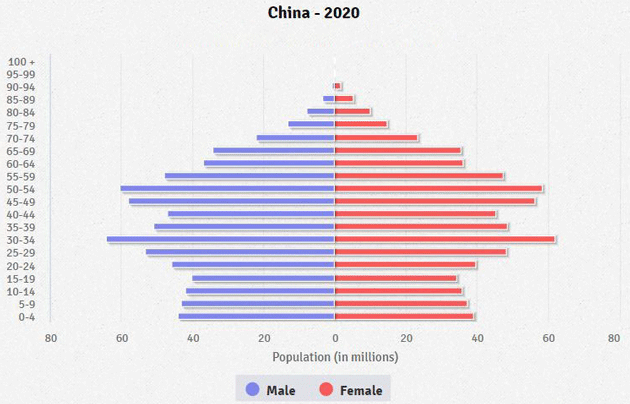

Further, China has a serious demographic problem. The one-child policy instituted in 1980 really kicked in around 1990, as you can see in the population pyramid below.

Source: Index Mundi

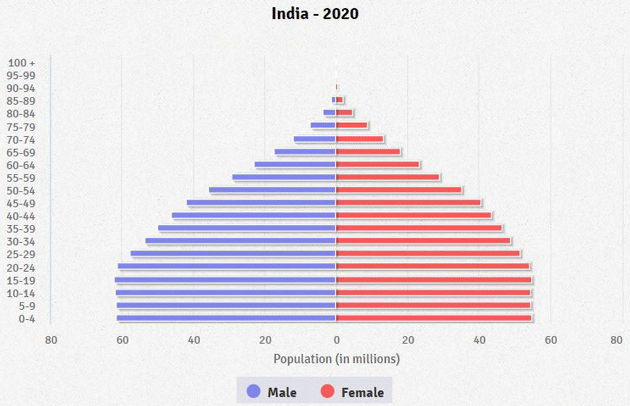

Normally, population pyramids are actual pyramids. Let’s look at India as an example. This is a population pyramid.

Source: Index Mundi

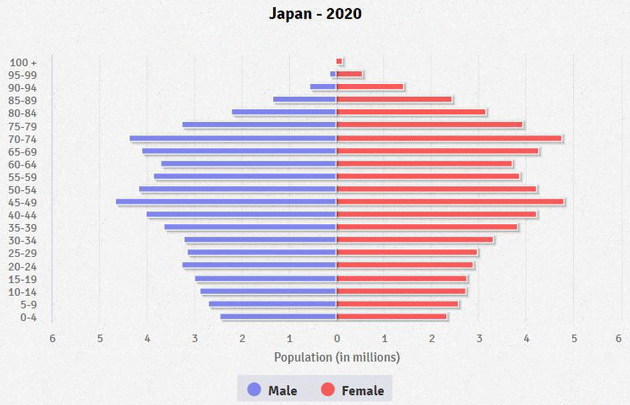

While we are on this, let’s look at Japan:

Source: Index Mundi

Japan has similar demographic characteristics to China, but with one huge difference. Japan grew rich while it grew older. China has grown older before growing rich.

All countries have problems,

but even with all its impressive growth and infrastructure, China has more. Which to me makes it more

dangerous.

The SEC is correctly insisting on audits for Chinese

companies listed on US exchanges. I personally think we should ban new Chinese

listings unless they agree to US audit standards. Kicking out currently-listed

Chinese companies will be trickier, as US investors don’t actually own the

shares many think they do. We don’t want to blow a $2 trillion hole into US

investor assets.

US corporations need

to rethink how they approach China. For some, there will be few issues.

For others? Real problems.

This week the Biden administration warned US companies about

doing business in Hong Kong. China has essentially removed the rule of law that

enabled Hong Kong’s financial activity. The US advisory reportedly

cites the risks of electronic

surveillance and having to surrender corporate and customer data to the

government.

.

Xi apparently

thinks that it is time to forgo access

to the US markets. Maybe he thinks Chinese

companies can list in Hong Kong and Westerners will still invest. Maybe. Then

again, maybe not.

Rule of law should be critical to any right-thinking

investor. When the CCP can nudge an auditor to give a thumbs-up or thumbs-down

based on some concept of social credit, how can you trust their assurances?

Will that happen often? We don’t know. But we know it’s possible.

I’m not saying avoid China entirely, as there are still

opportunities. But you should have your eyes wide open and understand the

risks. I would prefer China-exposed US

or other Western companies that give you real audits and normal shareholder

rights.

China is going to be a massive headache for the world

over the next few decades.

Washington DC, Maine,

and Colorado

I plan to go to Washington DC for a few days before heading

out to Bangor, Maine, and then Grand Lake Stream for Camp Kotok, the annual

fishing and economic fest. This year my youngest son Trey (who is now 26) will

once again accompany me, which he has done for most years since he was 12. Then

I will go to Steamboat, Colorado, for a speaking engagement before heading

home.

The problems in Cuba are a topic of interest here in Puerto

Rico. Interesting conversations. People ask why the US turns away Cubans

fleeing political unrest and persecution but accepts those fleeing Central

America for similar reasons? I don’t have a good answer, at least one that is

politically correct.

We also talked about entrepreneurs. The Cuban community in

Florida is nothing if not entrepreneurial. They have been a huge plus to the

local and national culture. Growing up with immigrants (legal and illegal) from

mostly Mexico, I would argue that they have also contributed to a vibrant

culture within Texas and the border states. I have consistently been

pro-immigration for 40 years. I want risk-takers and freedom-lovers from all

over the world, especially those with education and talent, to share in the

American experiment.

And with that, I will hit the send button. Have a great week

and remember where your ancestors came from. Most of us came from risk-taking

immigrants.

Your needing more space to talk about China analyst,

John Mauldin Thoughts from the Frontline

John Mauldin

No comments:

Post a Comment