CityLab University: Understanding Homelessness in America

As economic disruption threatens to trigger a spike in housing instability, here’s an essential primer on the causes and consequences of a thorny urban problem.

It’s time again for CityLab University, a resource for understanding some of the most important concepts related to cities and urban policy. If you have constructive feedback or would like to see a similar explainer on other topics, drop us a line at citylab@bloomberg.net.

As it has in so many other arenas of American life, the coronavirus pandemic has exposed the depth and severity of the nation’s homelessness crisis. When governors and mayors delivered stay-at-home orders, many Americans—likely more than one million—had nowhere to go. Suddenly, the plight of those living on the streets became intimately linked to the well-being of everybody else as the nation sought to tamp down a contagion that targets the most vulnerable members of society.

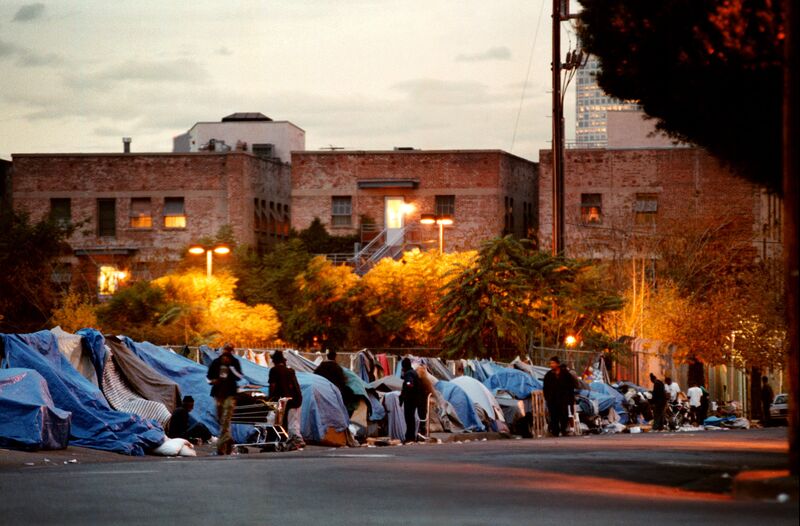

This edition of CityLab University seeks to provide a baseline level of knowledge about homelessness, a phenomenon that has long been linked to urban life in the United States. That’s been particularly true in cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York City, where scenes of tent encampments and panhandlers amidst urban wealth provide a stark illustration of urban inequality. The coronavirus crisis stands to exacerbate the problem, perhaps dramatically: According to a recent study, the economic disruption, housing instability, and mass unemployment that Covid-19 has touched off in the U.S. could lead to a 45% spike in overall homelessness within one year.

What are the forces that create homelessness? What are the main strategies aimed at helping people exit homelessness? What are the major debates that could shape this policy discussion going forward, especially in light of Covid-19?

This piece is focused on the experience of and policies related to people who have already become homeless. The next edition will cover the landscape of policies related to affordable housing and keeping tenants stably housed.

A Brief History of Homelessness in America

The first major wave of urban homelessness in America came after the Civil War, as jobless veterans struggled to find formal, permanent housing in increasingly crowded cities. Millions of those freed from slavery also experienced homelessness in the wake of the war; in the former Confederacy, vagrancy laws were enacted as part of the Southern “Black Codes” that allowed authorities to arrest anyone who appeared to be unemployed—an early American example of how poverty, race, and the criminalization of homelessness are intertwined.

In major cities, most homeless men found shelter in the skid rows that were emerging at the end of the 19th century—said to be named after a street in Seattle where logs were sent skidding down the road to port. The prototypical Skid Row was Manhattan’s Bowery, where short-term, dormitory-style hotels or lodging houses, known colloquially as flophouses, provided shelter to as many 75,000 men per night. The largely male residents of skid rows were often seasonal laborers working in extractive, maritime, transportation, and agricultural industries, moving between big cities and work sites by hitching rides on freight trains. Women and children on the brink of homelessness were generally able to stay away from skid rows thanks to services from charitable religious organizations.

The male-dominated, skid row-centered version of homelessness persisted for the next century or so, with peaks during industrial transformations, economic downturns like the Great Depression, and in the wake of wars.

But in the 1950s and ’60s, a chain of events began that would change the face and the meaning of homelessness in America. Many skid row lodging houses and other forms of unsubsidized affordable housing, especially in minority neighborhoods, were demolished as part of urban renewal. Regulations meant to decrease crowding and improve living conditions at the remaining lodging houses, which by then had become known as single room occupancy hotels (SROs), further eroded the supply of this housing of last resort. In the decade following 1973, over one million SRO units were lost to demolition or conversion to other uses.

Another well-intentioned effort—the deinstitutionalization of mental health patients—began in the mid-1950s with the introduction of effective antipsychotic medications and continued with the rise of “Great Society”-era improvements to social services and federal programs like Medicare and Medicaid. But this process of reforming psychiatric practices and closing the massive psychiatric institutions of the early 20th century ultimately left many vulnerable people at risk of becoming homeless. From 1950 to 1970, the patient population of national, state, and county psychiatric institutions decreased from over one million to less than 100,000. Today, prisons and jails have become the nation’s de facto psychiatric institutions.

Later, disinvestment in public housing and other housing programs—the HUD budget has never reached 50% of its 1978 budget, normalized for today’s dollars—forced more low-income people to compete in the Darwinian private housing market. The dismantling of the welfare state during the Reagan administration and beyond, including reduced public assistance for families, and work requirements for food stamps, squeezed many households. Widening economic inequality stemming in part from deindustrialization created a growing “service class” of people living paycheck to paycheck, with few opportunities for upward mobility.

By the 1980s, researchers, policymakers, and everyday city dwellers had taken note of a new form of homelessness. The “new homeless” are much more likely to be women, families, and minorities, especially African Americans. They are much less likely to be sheltered, whether in an SRO, public housing, or in overcrowded apartments—the places where extremely low income and intermittently homeless people had historically been able to find shelter.

Many of the forces that produced the new homelessness have been ongoing since the 1980s. Mass incarceration created generations of people with criminal records, the large majority of whom are Black or Latino, who have been essentially locked out of job and housing markets, leading many from prison to homelessness. The AIDS crisis that ravaged the LGBTQ community only added to the insecurity of a group wherein many people are forced to flee stable circumstances just to be themselves. Successive drug epidemics, lack of access to medical care, and exponentially increasing medical costs have continued to push people into homelessness.

Compounding all of this, the economic revival of cities, gentrification and strict zoning rules that make it impossible for housing construction to keep up with job growth have made it incredibly difficult for lower-income people to afford housing in the places with the most opportunity. The single biggest factor that distinguishes the new homelessness from previous iterations is the high cost of housing. Before the 1980s, “There were people with mental illness, lots of people with substance abuse disorders, lots of poor people, all the same issues, but there was not widespread homelessness,” said Nan Roman, CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness. “What changed was the housing.”

This harrowing litany of forces stands in stark contrast to the widespread perception, encapsulated by President Reagan during a 1988 farewell interview, that many people are “homeless, you might say, by choice.” This narrative, like the notion that homelessness is the result of personal failings, is an oversimplified answer to an incredibly complex problem.

While the contours of the problem, and its potential solutions, can be sketched out, homelessness is ultimately a varied and unique individual experience, produced by a mix of personal and external forces. “A housed person has never been through anything like this. They can’t relate,” said Ducky, an unsheltered homeless man living in San Francisco’s Civic Center. But, he added, “They can try. They can try to have sympathy.”

How many people are experiencing homelessness in America?

The homeless population is extremely difficult to measure, since homelessness takes so many different forms. The most widely used measure is HUD’s Point in Time (PIT) count, which identified 567,715 homeless people on a single night in January 2019. About 63% of individuals counted were sheltered, and 37% were unsheltered.

There are many indications that the actual number of homeless people is much higher. The National Coalition for the Homeless points out that the PIT count largely misses recently homeless individuals staying in supportive housing, which is paid for with federal and local homelessness funds. In 2017, this population added up to 503,473, pushing the total number of homeless people in the U.S. above 1 million. The fact that the PIT count always takes place in January is also thought to depress the results, as people exhaust their resources and connections to find shelter during the coldest time of the year.

Additionally, the PIT count doesn’t account for people who are precariously housed, shuffling among friends and relatives, and sleeping in cars or on the streets when good will dries up. When the Chicago Council on Homelessness counted families that were “doubled up” in individual housing units, they found that more than 80,000 people were homeless in the city at some point in 2015, in contrast to that year’s PIT count of less than 6,000. The U.S. Department of Education, which uses a more expansive definition of homelessness, estimates that more than 1.5 million public school students experienced homelessness during the 2017-2018 school year. In this wider universe of homeless individuals, few people interact with the homelessness services ecosystem.

What are the key geographic and demographic trends in homelessness?

The last three years have seen small increases in the national homeless population, with somewhat more significant gains in the past year, after years of declines following the Great Recession. However, overall trends have been highly divergent across geography, with some expensive coastal cities and states seeing big increases, and more affordable locales seeing major declines.

Nationwide, according to HUD PIT counts, the homeless population decreased 12% between 2007 and 2019. But New York State saw a 47% increase over that period, and Massachusetts and Washington, D.C., saw increases of greater than 20%. Florida, Texas, Georgia, New Jersey and Illinois saw reductions in their homeless populations of greater than 30% over that period. Notably, Massachusetts, New York, and the District of Columbia all have “right to shelter” laws that legally obligate the government to provide shelter for every homeless person, which means these jurisdictions likely have a more accurate estimate of their homeless populations. (More on right to shelter in the “debates” section.)

California is in many respects a world unto itself when it comes to homelessness. Of the state’s 150,000 or so homeless people, more than two-thirds are unsheltered, accounting for nearly half of the nation’s unsheltered homeless population. In 2016, California hosted 40% of the nation’s homeless encampments, and in 2019, the state was home to 40% of the nation’s chronically homeless population—people who have been homeless for at least 12 months and can be diagnosed with a substance abuse disorder, mental illness, or a physical or developmental disability. About one quarter of the nation’s unhoused population are thought to chronically homeless.

Homelessness cleaves with other forms of disadvantage. Native Americans,

Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and African Americans experience homelessness at significantly disproportionate rates. African Americans experience homelessness at a rate five times greater than whites. Research from the National Alliance to End Homelessness attributes this discrepancy to longstanding discrimination in the rental housing market, in the criminal justice system, in the healthcare system, and even in the homelessness service ecosystem.

People who identify as LGBTQ are another over-represented demographic among the homeless: About 40% of unsheltered youth nationwide identify as LGBTQ. Unsheltered homelessness among people who identify as transgender increased 43% between 2018 and 2019, and a staggering one in five transgender people have been homelessness at some point in their lives.

Families and veterans are among the demographics that have seen the greatest reductions in homelessness in recent years. Veteran homelessness has declined 40% since 2009, thanks to targeted initiatives like the Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing Program. (The federal government spends six times more per person on veteran homelessness than civilian homelessness.) Family homelessness is down by more than 25% since 2007, with the unsheltered population decreasing by nearly 75%. Notably, ending family and veteran homelessness were two of the specific goals identified by the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) Opening Doors initiative, adopted in 2010, indicating that increased resources and attention really does decrease homeless.

What causes people to fall into homelessness?

A 2007 academic study called “Ending Homelessness in Los Angeles,” which included a detailed survey of homeless residents of LA’s Skid Row, identified three broad categories that precipitate individuals’ fall into homelessness: loss of material resources, loss of family or social connections, and loss of health. These categories often overlap: 22% of respondents lost their dwelling, 18% lost their job, and 12% lost welfare benefits. Domestic violence was cited by 14% of respondents, while 7% noted an inability to find shelter, often due to release from prison. Sickness or injury were cited by another 12%; drug or alcohol problems by 8%.

Among women and families with children, domestic violence is a leading cause of homelessness. Programs designed to assist survivors of domestic violence are not adequate for the scale of the problem: In their one-day survey for 2019, the National Network to End Domestic Violence found nearly 8,000 people fleeing domestic violence who sought housing and emergency were not able to get it.

Most studies show that substance abuse, physical and mental disability are more common among homeless people than in the general population. The Brain and Behavior Research Foundation estimates that at least a quarter of homeless people are severely mentally ill. A 2003 study from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration found that 38% of homeless people were dependent on alcohol and 26% used other drugs.

However, it’s often difficult to say whether or not these conditions precipitated an individual’s fall into homelessness, since the brutal experience of homelessness itself can so easily exacerbate them. Additionally, treatment for addiction or mental illness, as well as other health conditions, becomes very difficult when an individual is living on the street.

These factors exist before the backdrop of a huge shortage of affordable housing. The National Low Income Housing Coalition has calculated a nationwide shortage of more than 7 million homes affordable to those with extremely low incomes. This cohort lives on the brink of homelessness, and any number of factors could push them over the edge, especially in the most expensive cities. A 2018 Zillow study illustrates this connection, showing how rising rents are a strong indication of increases in homelessness.

Who provides homeless services? How are they funded?

Federal funding for homelessness services were initiated by the McKinney-Vento Act of 1987, which removed permanent address requirements for certain government benefits and created grant programs for emergency shelters and transitional housing. The McKinney-Vento Act also created the USICH to coordinate federal homelessness programs. It remains the only major federal legislation specifically addressing homelessness.

Since 1995, the federal government has required communities to apply for federal funds in a single application as a Continuum of Care (CoC). These jurisdictions are responsible for identifying their geographic region’s homelessness needs and coordinating the provision of services among the many providers. CoCs can be as small as cities, like Pasadena and Long Beach, or as large as a state, like Maine and Montana.

The federal government doles out resources to CoCs based on their applications, as well as local PIT counts. In 2020, HUD is slated to give out $2.2 billion in grants to CoCs. In some jurisdictions, these funds account for the majority of government homelessness expenditures. In cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles, which receive funds from multiple state and local homelessness ballot initiatives, federal funds represent a relatively small proportion of the total.

Government funds flow to a variety of public sector programs, nonprofits, and faith-based organizations (FBOs) that provide homeless housing and services. FBOs, many of which are part of large networks like Catholic Charities and CityGate Network, provide about 30% of the nation’s emergency shelter beds, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. Another study from Baylor University found that FBOs accounted for nearly 60% of shelter beds across 11 geographically diverse major cities. Southern and Midwestern cities tend to have higher percentages of FBO-provided shelters, and West Coast cities have lower percentages. The study also notes that churches and other faith-based groups often provide informal support for community members on the brink of homelessness.

Where can homeless people find shelter?

The first and best way to combat homelessness is to keep people from becoming homeless in the first place. Rent controls, eviction protections, rent vouchers, subsidized housing and other mechanisms that fulfill this purpose will be discussed in the next edition of CityLab University. Below are the primary ways people who have already become homeless can find shelter.

Temporary or emergency shelters are intended as facilities for short-term stays, and do not require residents to sign lease agreements. They often include dormitory-style sleeping quarters. Low barrier shelters follow the harm reduction model, imposing few rules and restrictions on those who need shelter. Other shelters, often those operated by FBOs, have more strict rules related to things like substances, pets or partners.

Navigation centers are low barrier shelters with case managers who work with residents to connect them with permanent housing, healthcare, and other services. Some cities refer to this practice as coordinated entry, ensuring people who enter the homelessness service ecosystem are connected with services that fit their needs.

Informal or unsanctioned encampments are groups of tents and makeshift dwellings, sometimes including RVs, set up in unauthorized locations. A report from the National Law Center for Homelessness and Poverty found that media mentions of homeless encampments increased more than 1,000% between 2007 and 2016, even as official homeless counts decreased.

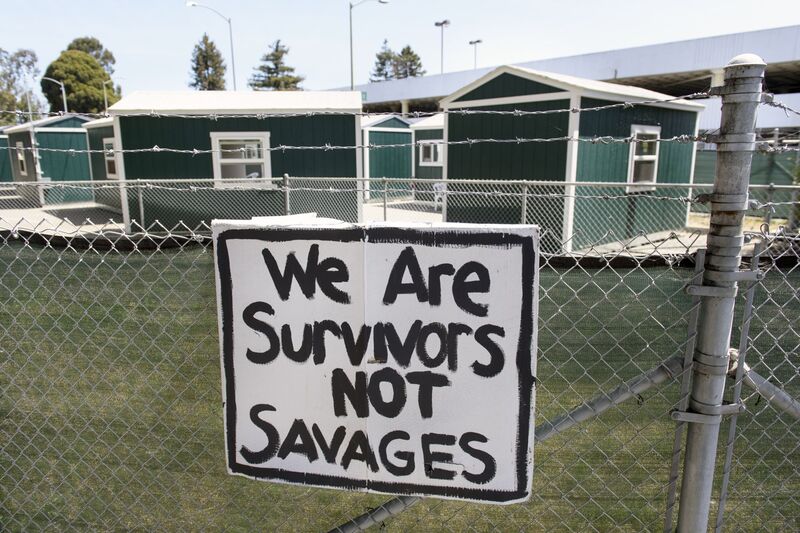

Sanctioned Encampments are groups of non-traditional dwellings that are legally permitted and often financially supported by local governments. Oakland has installed tiny homes—cheap, simple, quick to construct cabins—in five city parking lots, with bathrooms, security and other services. Portland’s Dignity Village has been operating as a city-sanctioned “intentional community for the homeless” since 2000. In recent years, safe parking facilities with bathrooms and security have become more common as a response to the rise in vehicular homelessness.

Single room occupancy hotels and apartments (SROs) were the catch-all term given to lodging and boarding houses beginning in the 1930s. They typically consist of small single rooms with shared bathrooms and no kitchen facilities. While a comparative rarity today, they still serve as a key source of extremely low-income housing. San Francisco, for instance, still has 30,000 SRO units, mostly owned by nonprofits.

Transitional housing is short-term housing (anywhere between two weeks to two years) connected to services designed to help people permanently exit homelessness. Transitional housing facilities are often congregate housing settings, similar to emergency shelters. A USICH report found that this form of housing was most effective for specific demographic groups, including survivors of domestic violence, and youth. Transitional housing beds for the general population have decreased in every state since 2013.

Permanent supportive housing is designated for chronically homeless people with disabilities or severe substance abuse issues, with wraparound healthcare and other supportive services.

What are the key laws governing homelessness policy?

As modern homelessness has grown, so have the number of laws targeting homeless people. Quality of life ordinances—such as sit-lie laws regulating individuals’ right to sit or lie on public property or panhandling laws regulating individuals’ right to ask for money in a public place—have increased significantly over the past decade. (Hostile architecture accomplishes these same ends with design, placing spikes or boulders in places where homeless people sleep or hang out.) Researchers from the Western Regional Advocacy Project have connected quality of life ordinances to the broken windows theory of policing, as well as discriminatory laws from the past, like Jim Crow-era “Sundown Towns.”

In many cities, police function as the first-line homeless service providers, and jails as de-facto homeless shelters. Dallas police issued more than 11,000 citations for sleeping in public between 2012 and 2015. Last year Los Angeles voided almost two million minor warrants and citations to save the courts money and make it easier for homeless people to get back on their feet.

Anti-homeless laws are facing significant challenges. The National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty argues that the 2015 Norton vs. Springfield appellate court ruling, which found that the Illinois capital’s downtown panhandling ban unconstitutionally violates freedom of speech, invalidates many existing panhandling laws. The recent Boise vs. Martin decision creates new legal protections for people sleeping outdoors when there is no shelter bed available to them. This decision, which the Supreme Court let stand in December 2019, has huge implications for cities’ approach to unsheltered homelessness.

A lack of enforcement is another dimension of homelessness and the law. Historic skid rows and other low-income neighborhoods in major cities have become “containment zones,” where the police are less likely to enforce low level quality of life laws. These areas can be a refuge for the homeless, providing a critical mass of services and relative security from police harassment. However, housed neighbors and merchants in these under-privileged communities often call these tacit arrangements unfair.

What are the major debates in homelessness policy?

The “right to shelter” laws in force in cold weather states like Massachusetts and New York have been criticized as a Band-Aid that makes homelessness less visible, potentially decreasing political will for permanent housing and services proven to help people exit homelessness. Additionally, the fact that people are legally compelled to enter shelters that may not be the most pleasant, sanitary, or safe places brings up civil liberty concerns. Conservatorship, which gives the government the right to compel mentally ill people to accept medical treatment, is another homelessness policy that has brought up similar concerns.

Critics of right to shelter and other policies that emphasize short-term, emergency shelters tend to be aligned with the “Housing First” approach to homelessness. This philosophy seeks to get homeless individuals into permanent housing—not shelters or transitional housing—as quickly as possible, without barriers like requiring sobriety. The idea is that underlying issues like addiction, mental illness, and physical disability cannot be properly addressed without having a stable home environment; neither can someone be reasonably expected to get and hold a job without having a safe, clean home to return to.

In recent years, Housing First has become a widely accepted principle in the homelessness services community, strengthened by HUD’s embrace of this approach during the Obama administration. This pivot has alienated many faith-based organizations, which are key providers of short-term emergency shelters, as already limited funds are diverted to permanent housing programs. They now have an ally in President Trump’s homelessness czar, Robert Marbut Jr., who currently leads the USICH and has been a vocal opponent of Housing First.

While evidence overwhelmingly suggests that Housing First is the most effective way for people to exit homelessness, it takes a long time, and a lot of money, to build said housing. In the meantime, there remains a huge imbalance between the number of unsheltered homeless people, especially in warm-weather states like California, and the number of available shelter beds. The Boise decision could force cities and states to move more quickly to close that gap.

Addressing the shortage of either shelter or deeply affordable housing can be difficult due to NIMBYism from housed neighbors. In many cities and neighborhoods, local residents have significant power to delay or block badly needed shelter beds and housing, often basing their opposition on spurious stereotypes about increases in crime or trash surrounding such developments.

Housed neighbors, city officials, and homeless individuals and their advocates also clash over informal, unsanctioned encampments. City officials are often under significant pressure from neighbors, and sometimes health and fire authorities, to disperse these encampments. However, when encampment sweeps do occur, they often result in the confiscation and destruction of valuable property, including essential medication. Due to the shortage of shelter capacity, encampment residents are often forced to simply move their camp to another location, starting the process anew. The National Coalition for the Homeless recommends cities follow Indianapolis’ encampment sweep policy, which requires 15 days notice before a sweep, and requires that campers’ personal belongings are stored for at least 60 days before being thrown away.

Will Covid-19 change the homelessness policy landscape?

To put it mildly, the coronavirus pandemic has created unprecedented new homelessness policy challenges. Living on the streets puts people at a greater risk: One study from the Coalition for the Homeless found that the age-adjusted Covid-19 mortality rate among homeless New Yorkers living in shelters was 61% higher than that of the general population in the city.

“It demonstrates that homelessness is a public health issue as well as a housing issue,” said NAEH’s Nan Roman. “Having so many people living outside and in congregate spaces has public health implications.” In many cities, the short-term solution to dispersing congregate settings has been housing the most at-risk homeless individuals in hotels—although some advocates criticized these efforts for not being fast or decisive enough. Longer term, shelters are being reconfigured to create more distance between residents. And cities like San Francisco, which previously did not permit tent encampments of any kind, has established sanctioned encampments where social distancing can be enforced.

Roman and other homeless advocates are concerned that once coronavirus-related rent and mortgage forbearance policies expire, many more people could be driven into homelessness. The NEAH and other groups are currently advocating for a $100 billion rental assistance package to help ensure that doesn’t happen. Other housing advocates are calling for rent and mortgage payments to be fully canceled as long as the crisis persists.

Another looming question is what will happen to homeless individuals currently housed in hotels, once FEMA or city-owned leases expire, and shelters are still operating at reduced capacity. Some advocates hope this crisis will push the government to purchase hotels and homes owned by corporate landlords and Airbnb operators in order to convert them into to permanently affordable housing. California Governor Gavin Newsom announced that the state plans to pursue this option for some of the hotels that, as of early July, about 14,000 homeless Californians.

For those who have been studying and struggling to find solutions to homelessness, the housing instability that the coronavirus has triggered could finally expose the full extent and seriousness of this long-ignored social problem—and perhaps create the impetus for policy changes that advocates have long pushed. “The pandemic is said to be an emergency, and it is,” as cultural geographer Don Mitchell told CityLab’s Mimi Kirk recently, “but we’ve already been living in an emergency.”

Sources and further reading

Flophouse: Life on the Bowery, by David Isay and Stacy Abramson

Down and Out and On the Road: The Homeless in American History, by Kenneth L. Kusmer

Mean Streets by Don Mitchell

“Ending Homelessness in Los Angeles” by Jennifer Wolch, Michael Dear et al.

“The Rise of Homelessness in the 1980s,” KCET

Permanent Supportive Housing: Evaluating the Evidence for Improving Health Outcomes Among People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness, National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine

“Swept Away: Reporting on the Encampment Closure Crisis,” National Coalition to End Homelessness

“State of Homelessness, 2020” National Alliance to End Homelessness

“Housing First” National Alliance to End Homelessness

“The 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

“Without Housing Fact Sheet,” Western Resources Advocacy Project

No comments:

Post a Comment