Disease, Finance and Unintended Consequences

What will be the long-term consequences of the pandemic? Few if any answers are clear. In the financial realm, markets have automatic checks, balances and stabilizers. Tracing the impact of the last few months into the future soon becomes like plotting out an attack in chess. You can try to predict how the opponent will react, but you cannot know. A few unexpected moves could end your strategy. With this in mind, here are two historic pandemics whose financial ramifications were hard to predict at the time.

Potato Blight:

The disease that started to spread through the Irish potato crop 175 years ago would lead to appalling suffering, and changed the course of history. Without the Potato Famine, it is unlikely the U.S. would have benefited from the influx of Irish immigrants who went on to hold great influence. Three presidents to date have been descended from migrants who fled the famine; Kennedy, Reagan and Obama. Joe Biden would be a fourth.

Without the famine, the progress of Irish independence from the U.K. would almost certainly have been different. Ireland’s Civil War, the Troubles in Ulster, and the writhing over Brexit might all have been altered. Demographically, the impact of the famine and the emigration it spurred can still be felt. Last year, Ireland had 4.9 million people — the most in more than a century, but still below the 5.1 million recorded in 1850. Over the same period, the population of England and Wales rose to 59.4 million from 17.9 million.

This episode played out in the home territory of what was then the most powerful country in the world. How could this have been allowed to happen? From the first, historians have come up with starkly differing explanations. Plausible comparisons have been made to the Holocaust, with Irish historians arguing that the British were guilty of deliberate genocide. Tony Blair, when U.K. prime minister, made a formal apology to Ireland for doing too little; but the free-market theorists at the Mises Institute suggest that “the English government was guilty of doing too much.” Had they not intervened in the workings of the free market, the libertarian argument goes, Ireland would have dealt with the epidemic far better.

But one of the most interesting ideas I have heard comes from the Cambridge historian Charles Read in Laissez‐Faire, the Irish Famine, and British Financial Crisis. He discussed this with British historian Dan Snow on the History Hit podcast, which I thoroughly recommend. He argues that the British response was undermined by financial mismanagement that led to a crisis startlingly similar in its fundamentals to those of our time. In outline, it is clear that after Robert Peel gave way to Lord Russell as prime minister, Irish taxes were hiked, and grants became loans that would need to be repaid:

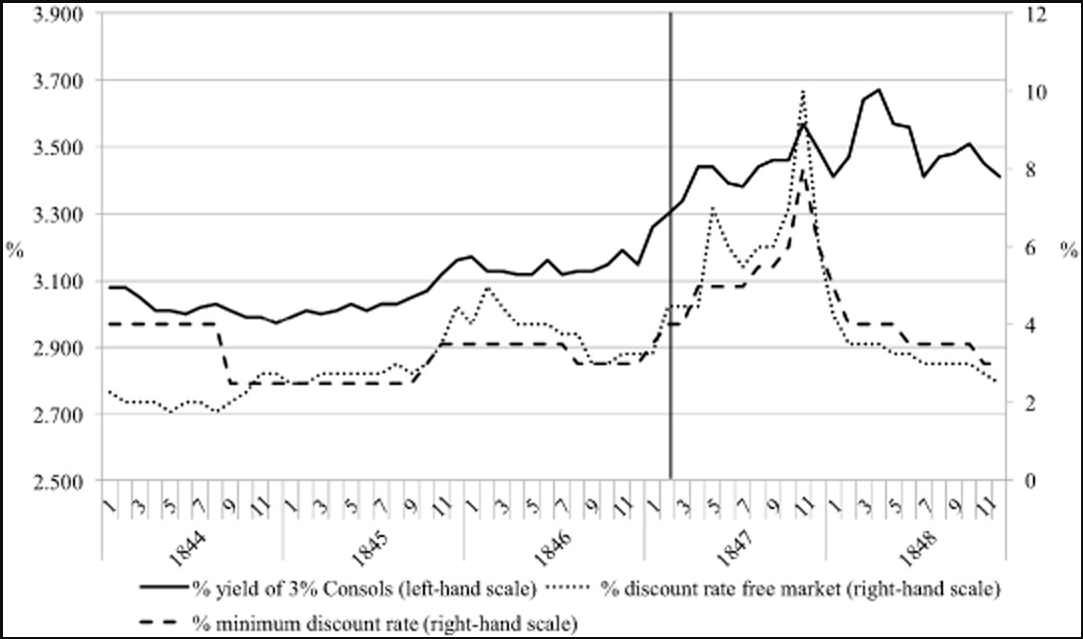

To be clear, nothing exculpates the British. But why exactly did they reverse course this badly? Read suggests we should blame the bond market. This is what happened to the interest rates on consols, which dominated Treasury lending at the time, after the government attempted to borrow more money to deal with the famine:

The bond market was in revolt. So was the gold market. Britain in those days was as financially dominant as the U.S. is now, but it didn’t have the exorbitant privilege of printing more of its own currency at will. It was still tied to the gold standard, and already had a lot of outstanding debt from its successful wars earlier in the century. So, as British politicians tried to raise money to fund the Irish relief effort, investors decided that they wanted their money from the Bank of England in gold, not paper:

The last six months would have been very different, and probably much more painful, had the dollar still been tied to gold. In the 19th century, the British resorted to putting the burden for the Irish relief efforts on to the Irish themselves, and hiked taxes many times over. The result was famine and death, and a mass emigration whose effects are still felt today.

Spanish Flu:

Covid-19 is arguably the worst pandemic since the “Spanish” influenza of 1918. Thankfully, the coronavirus has turned out to be far less deadly. But the after-effects of the Spanish flu suggest that the financial impact can be counterintuitive. You would think that an epochal pandemic would inflict terrible damage on the life insurance industry. But it didn’t.

A new research paper by Gustavo Cortes of the University of Florida and Gertjan Verdickt of Monash University suggests that the Spanish flu was a “blessing in disguise” for American life insurers. You can find a brief video on Twitter here, and the full paper here.

As might be expected, death claims rose sharply during the first year of the pandemic:

But importantly for the industry, they then fell sharply to lower rates than in much of the preceding decade. The disease had brought forward many deaths; after a bump in 1918, that left fewer fatalities than usual in the following years. Meanwhile, the pandemic ensured much stronger demand. People who might have tried to get by without insurance a few years earlier rushed to buy in 1919.

Life insurers’ shares, having been dented briefly while the pandemic was raging, made up all the lost ground within months of the end:

With investors able to see the near-term outlook was good, companies were able to raise far more money in equity offerings:

Meanwhile, new incorporations of life companies surged in 1919, again making it easier for the industry to absorb the impact of the pandemic:

With the potato blight, financial mechanisms magnified a public health crisis into a humanitarian and economic catastrophe. After the Spanish flu, financial markets helped the country minimize the damage. Bear this disparity in mind when trying to predict how they will deal with the aftermath of Covid-19.

No comments:

Post a Comment