Real estate is China's economic Achilles heel

It's the country's biggest engine of growth an employment, financial asset, and source of government revenue.

This is the second in a short series of posts about China’s economy. The first post, from last week, was entitled “Where China is beating the world”.

I once joked to a friend that if I were a CIA operative and I wanted to slow down China’s economy, I’d try to get everyone in the country to be obsessed with real estate. (The reason it was a joke is because the real estate obsession happened a very long time ago, and because I had just written a Bloomberg post about it.)

If you want, you can think of a country’s economy as composed of two pieces — the stuff the country sells to other countries (exports), and the stuff it sells to itself. Exports are probably disproportionately important, because of the local multiplier effect, and because they help raise productivity. Export industries generally have to be pretty competitive, since the competition pool is much bigger — as an exporter you’re going up against companies from all the most technologically advanced and business-savvy countries in the world. And in fact, we do find that productivity in manufacturing, which is generally more exposed to global competition since manufactured products are easy to export, tends to converge to global averages more rapidly than in other industries — it’s sink or swim.

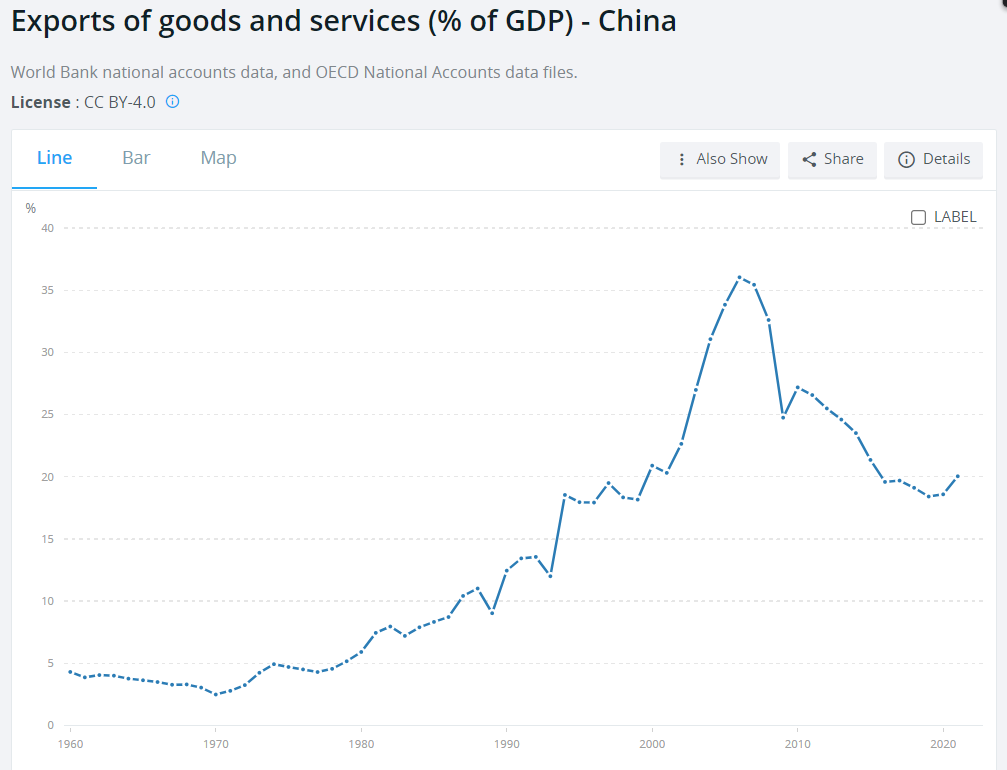

This is one reason why when we think of “what a country does” economically, we think of export products — Germany “makes cars”, Taiwan “makes electronics”, and so on. But for big countries, most of what that country does is to sell stuff to itself. China has a reputation as an export powerhouse, and it runs a big trade surplus, but exports are only 20% of its GDP, and that number has fallen in recent years.

So most Chinese people aren’t making your iPhone or whatever — most of them are focused on selling stuff to other Chinese people. And in China, an especially large proportion of what they sell to each other is real estate, or something related to real estate.

Real estate as economic engine and source of mass employment

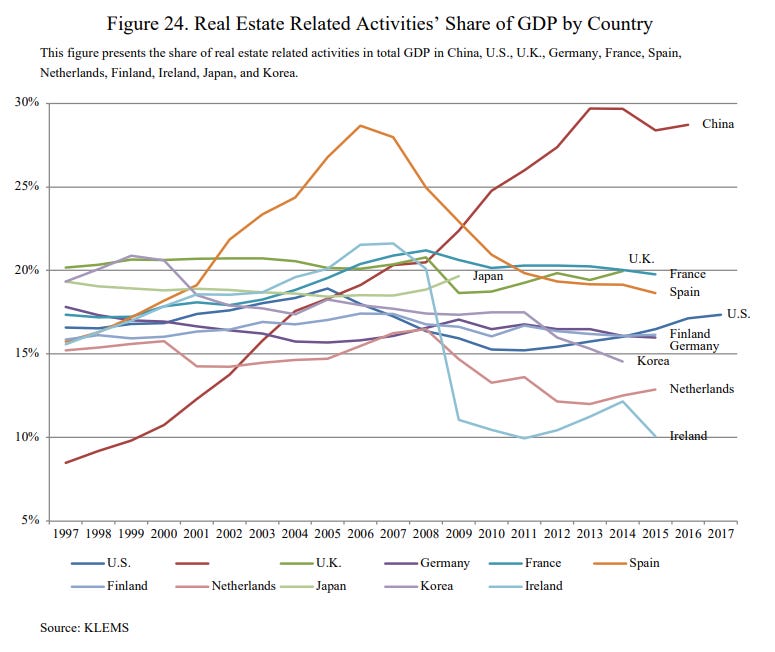

Here’s a famous graph from Rogoff and Yang (2020), which, along with Xiong (2023) and Liu and Xiong (2018), is one of my favorite papers for understanding real estate’s place in the Chinese economy:

Painting with a broad brush, you could say that China shifted from an export-led economy to a domestic-investment-led economy after 2008. And the biggest chunk of that domestic investment, by far, was real estate.

Real estate development and its related industries (such as real estate finance) don’t just create places for Chinese people to live; they also create vast amounts of employment in the Chinese economy. That’s a big problem right now, because in the wake of the real estate crash that began in 2021, China’s unemployment has risen a lot — officially, unemployment for the 16-24 age group is now at 20.4%, compared to 6.5% in the U.S. Having a vast number of unemployed young people is a threat to both social stability and the future quality of the workforce, and it’s definitely something that’s worrying the Chinese government right now.

That real estate bust, by the way, is still going on, and — as you might expect for a sector so large, it’s weighing heavily on the rest of China’s economy. The overall narrative about China’s recovery in early 2023 has been recovery from the Zero Covid policies of late 2022 — growth was forecast to bounce back to a rapid 5.2% this year. But the most recent monthly economic data shows that the troubles are far from over. Here’s Bloomberg:

China’s economic recovery weakened in May, raising fresh fears about the growth outlook…Manufacturing activity contracted at a worse pace than in April, while services expansion eased, official data showed Wednesday, suggesting the post-Covid rebound had lost momentum…

A stronger recovery in China will also depend on a turnaround in the property market, which makes up about a fifth of the economy when including related sectors. Home sales have slowed after an initial rebound, while real estate developers continue to face financial troubles.

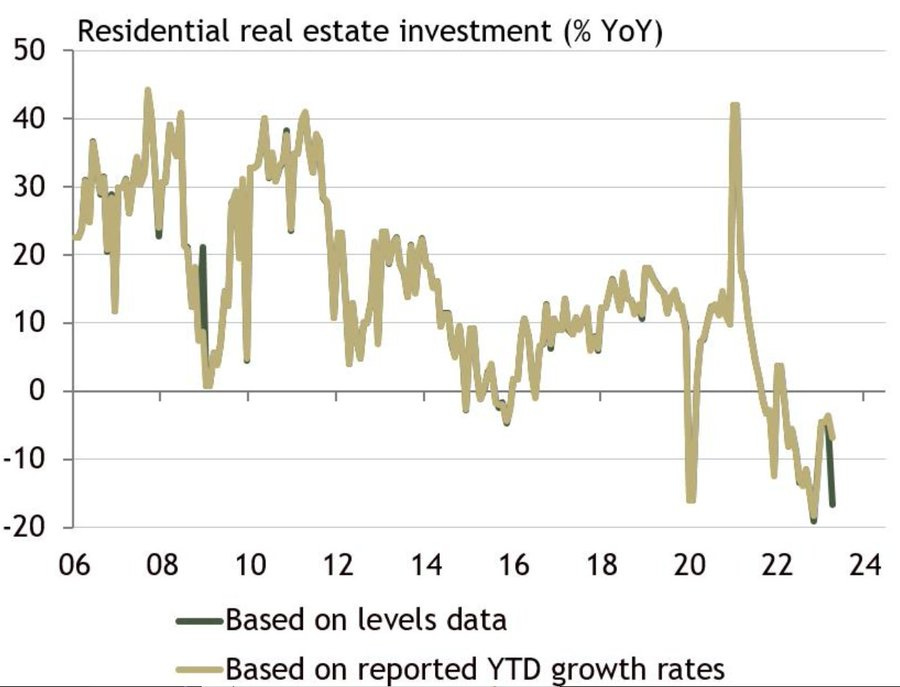

It’s highly likely that underneath the headline-grabbing drama of Zero Covid, the real force dragging down China’s short-term growth is the general crisis in the real estate sector that began a year and a half ago. That crisis is still ongoing, with more defaults coming periodically. As Adam Wolfe reports in a detailed thread, residential real estate investment is falling:

And that’s in spite of the Chinese government’s frantic efforts to revive the sector. In the past, China was able to use real estate as a form of fiscal stimulus that cost the central government very little — the government just called up the state-controlled big banks and told them to lend more, and the banks lent to property developers. That stimulus came at the expense of long-term productivity growth (since real estate tends to have lower productivity growth than other sectors), but it did prevent China from experiencing recessions for a long time. With the current crash, though, that policy looks to have reached the end of its rope.

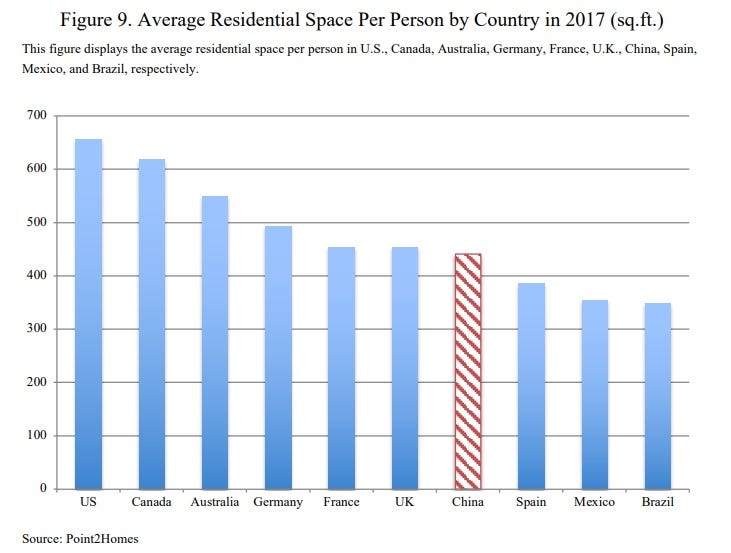

The fact is, China just doesn’t need that many more places to live. Even as of 2017 — six years ago! — China had already basically reached developed-country levels of living space per person.

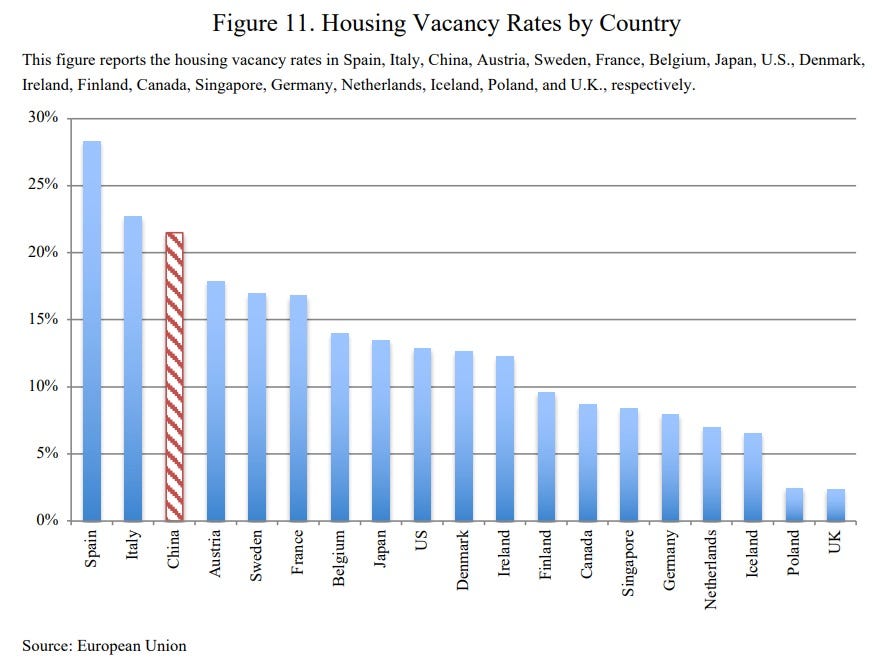

As China built more and more, vacancy rates rose steadily in all big cities except for the four “Tier 1” cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou). Overall, vacancy rates were significantly higher in China than in most rich countries:

That meant that China was building a bunch of real estate that nobody was really using as real estate. Instead, they were increasingly using it as an investment vehicle. Which brings us to the third major function of real estate in the Chinese economy: it’s the most important financial asset.

Real estate as financial asset

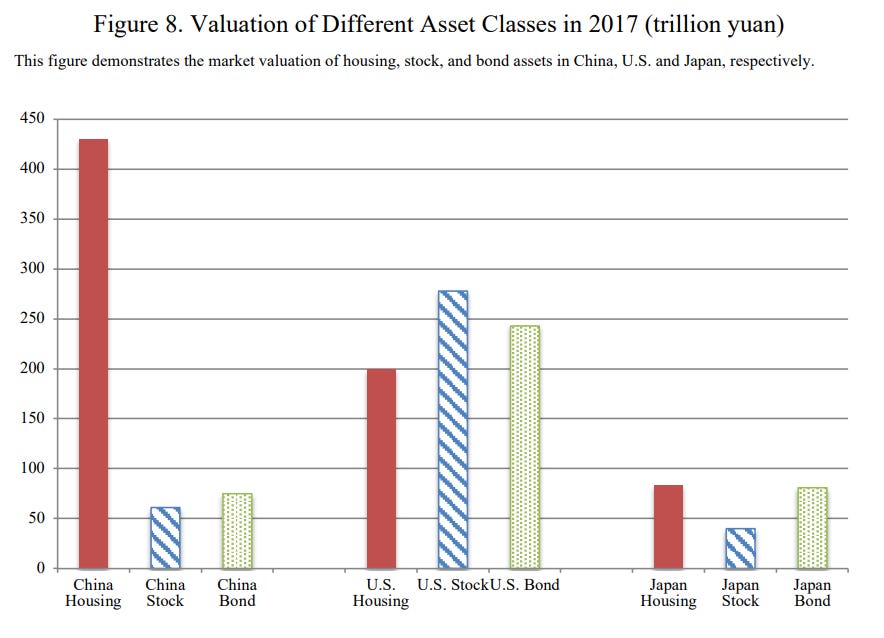

In any country, property will be an important component of wealth, alongside stocks and bonds. But in China, with its underdeveloped stock and bond markets, almost all financial wealth is real estate:

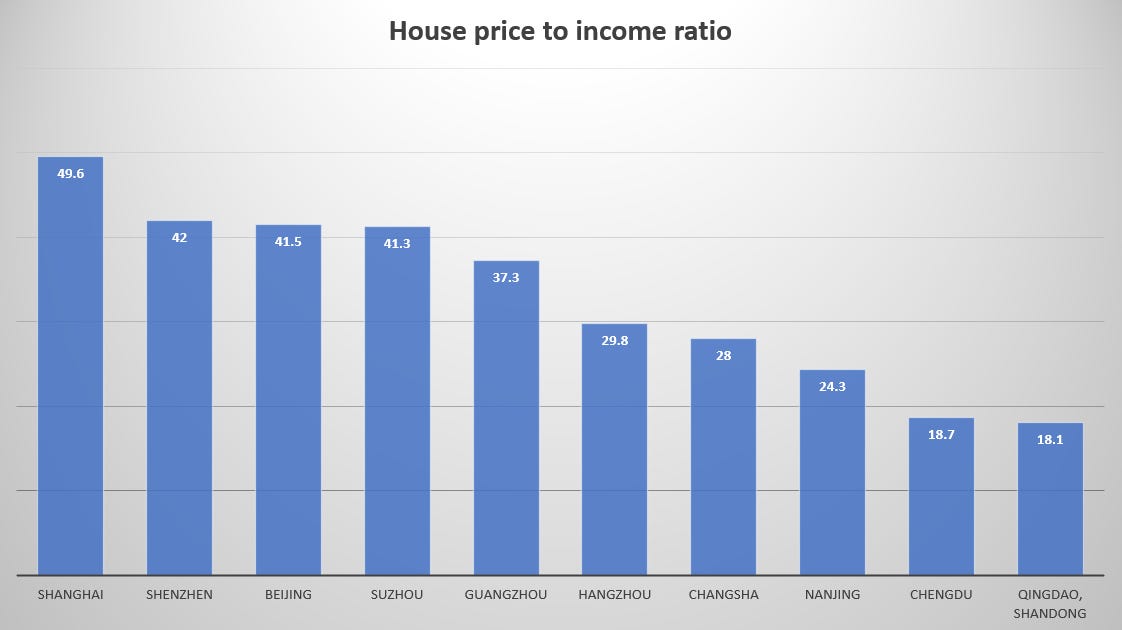

From looking at house prices compared to incomes, it’s clear that much of Chinese real estate is bought as an investment property rather than for its value as a place to actually live (and yes, this is speculative bubble behavior). In San Francisco — America’s famously least affordable big city — a typical house costs 10 times the typical resident’s annual income. In Chinese cities this ratio is often much higher:

Because real estate is China’s main financial asset, it’s crucial not just for determining what gets produced in China, but how the fruits of production get distributed. If your property values go up, or if a local government sells you some land cheaply, you’re a rich person; if your property values crash, you’re ruined.

As the real estate crash deepens, the distributional question is likely to roil Chinese society. Losses are being delayed and denied with various government support measures and cheap credit from banks, as well as simple refusal to sell. But the fundamental problem — that Chinese people paid excessive prices for real estate because they thought the price would always go up — remains. And that means that someone will eventually have to take the losses, either through writedowns or through inability to sell.

Regular households for whom property represents their retirement account will be pretty angry if they’re suddenly left unable to sell or forced to take a big loss. Meanwhile, a vast variety of local government officials and businesspeople will all be competing to make someone else take the losses. Because so much is at stake, that competition is likely to involve every trick in the book — government connections, business trickery of the legal and illegal kinds, and even abuses of government power. Here’s just one tiny hint at the mad game of “hot potato” that must be going on throughout all of China right now:

Xi Jinping is going to have to manage this situation very carefully. Of course he will want his own political allies to avoid losses, and make his enemies take as much of the loss as possible. But do that too much, and it could foment popular unrest. So the paper losses will be carefully spread around Chinese society, with the least powerful forced to take the greatest hit. Of course, the best solution for Xi would be if he could get foreign money to bail out the sector, such as the Western private equity firms with which China’s government is said to be increasingly cozy. But Western bailout cash will be limited in scope, so the thorny distributional problem remains.

Of course, real estate’s financial value also can affect production to some extent. Manufacturing companies are likely to use their real estate as collateral to get loans, and if the value of their collateral drops they could face a financing crunch and some might have to shut down. This famously happened in Japan in the 90s after their property bubble burst. I do expect China’s government to intervene to make sure manufacturing companies can get loans in strategic sectors, but there will probably be some sectors that won’t get government support and will experience big shakeouts.

The biggest losers from the real estate bust, however, will probably be China’s local governments.

Real estate as government revenue source

China’s local governments famously rely on land sales rather than on property taxes for most of their revenue. The real estate market is thus what allows local governments to both provide essential public services and to conduct local industrial policy — which, until the mid-2010s, was China’s main type of industrial policy.

If you want to read a good history of how that system evolved, I recommend the excellent paper by Liu and Xiong (2018). For a description of how the system currently works, and how much of China’s economic model depends on it, I recommend Xiong (2023). (In general, Wei Xiong is just one of the best economists around, and you will always come away a bit smarter from reading one of his papers.) This is from the latter paper:

The government controls the supply of land, which is the primary input for real estate development, and local governments use revenue from land sales to fund infrastructure and urban development projects…This hybrid structure allows the local government to provide infrastructure and public goods, facilitating local businesses and boosting economic growth and development…Since [2008], local governments have increasingly used debt to finance their operations. The debt financing used by local governments is typically collateralized by future land sales, land, or real estate properties[.]

Xiong explains that this system has a bunch of advantages and disadvantages. On the plus side, buying land in a city is basically like buying equity in that city — if the city government can produce local growth, your land price goes up. So businesspeople and homeowners all become shareholders in the city, which aligns everybody’s incentives toward growth. On the downside, the system creates a ton of different structural incentives for local governments to borrow too much, and for private investors to over-invest in un-economical and risky real estate projects, and for banks to finance these projects too cheaply. In other words, the combination of the local government sector and the property sector is a big reason why real estate looms so much larger in China’s economy than in other countries, and a big reason why the sector got so bloated.

Ultimately, relying on land sales to finance local governments is a strategy that just has a natural time limit. Eventually you run out of valuable land to sell. China’s local governments look like they’re hitting that point, which is why they’re increasingly asking the central government for money. And the central government is stepping in to replace the revenue from the lost land sales:

This means that many of the advantages that China got from federalism and local experimentation and initiative during its amazing growth boom in the 90s, 00s, and early 2010s will now be forfeit. Industrial policy will increasingly be conducted from the center; Xi Jinping and his clique will be making a lot more of the decisions regarding who builds what where, instead of partnerships of local governments and businesspeople. The virtuous cycle where the property sector aligns the interests of local governments and businesses toward growth will now be weakened if not broken altogether in many places.

China’s economy after the real estate boom

To sum up, although we tend to read mostly about Chinese manufacturing and exports, the real estate sector was at the very core of the country’s development model during the decades when Chinese growth wowed the world. It was simultaneously:

the largest source of economic growth, investment, and employment,

the main channel through which economic stabilization policy worked,

the country’s main financial asset and method of wealth distribution, and

the source of local government autonomy and experimentation.

In the wake of the crash that started in 2021, all of those roles will be much diminished. China will have to find a patchwork of solutions to replace these essential functions. It will have to boost domestic services to provide mass employment and growth, no matter how many cars and trains it builds. It will have to use traditional fiscal and monetary stimulus to fight recessions. It will have to develop its stock and bond markets more, as vehicles for wealth for both elites and the middle class. And it will have to shift to property taxation as a source of local government revenue, while increasing the role of the central government in both industrial policy and public services.

In other words, much of what made China’s economy special during its glorious decades was due to its unusual real estate system. Now that era is ending, and China is going to have to start looking much more like a normal developed country. If it fails to make that transition, difficult times could lie ahead.

No comments:

Post a Comment