| |

| FOLLOW US | GET THE NEWSLETTER |

A Holy Week ResurrectionLast week, which much of the world took to celebrate great religious festivals, turned out to be a great one for risk markets. Global stocks had their best week since the Lehman crisis of 2008, while the U.S., as judged by the S&P 500, had its best week since the Second World War. Meanwhile, junk bonds had their single best day on record. Roughly half of the market value lost during the Covid-19 crisis has been recouped. Could the bottom be in, and a new bull market already be underway? First, we should bear in mind that markets tend to move around a lot after a shock, and it would be surprising if we didn’t have another big move ahead. This illustration from Dec Mullarkey of Sun Life Capital Management shows that the VIX index is neatly retracing moves after the Lehman bankruptcy — when a further spike in volatility lay ahead:  With that caution in mind, we need to look at the two big reasons why the market has rallied so much. The first is that the virus news has been better than the worst fears. This raises hopes that the ultimate economic damage need not be so severe. The second is that the measures the Federal Reserve announced Thursday were so spectacular — involving buying even high-yield bonds and municipal debt — that it was dangerous to bet against the market. Those who underestimated the power of the Fed after 2008 refused to make that mistake again. So, does the (relative) success in fighting coronavirus mean a healthier economy ahead? And what will be the consequences now that the Fed has decided to “go for it”? From Mortal Hazard to Moral HazardIn the words of Olivier Blanchard, former International Monetary Fund chief economist, central banks have gone “from ‘whatever it takes’ to ‘Gosh, what have we done?’’” The Fed has gone much further than ever before by standing ready to buy high-yield bonds. The impact has been immediate, as Bloomberg Opinion contributor Jim Bianco of Bianco Research shows in these charts. Investment-grade spreads previously were wider than at any time since the 2008-09 crisis. Now they are within the range since then:  Meanwhile, high-yield or junk bond spreads had their greatest tightening in a single day on record (even though the Fed will only buy “fallen angels” that still had investment-grade status when the Covid crisis broke):  We can say with some certainty that it would have been good to be holding U.S. credit Wednesday night. Beyond that, it gets complicated. At one level, there is the issue of “moral hazard” — that bailing out bad debtors will remove the incentive from others to avoid trouble. In a crisis, such concerns often have to go out of the window. That was the painful lesson from allowing Lehman Brothers to go bankrupt. But central banks and others should still be careful about the precedents they set. Already before the Covid crisis, the U.S. was stalked by a record number of zombies — companies whose total tangible assets aren’t enough to repay all their debt. They can only stay alive with the help of rock-bottom rates. The economy would be more dynamic if they were allowed to fail, letting new companies arise. Moral hazard isn’t just theoretical — it leads to bad allocations of capital. That’s why the Wall Street Journal’s opinion page really hates this rescue package. There’s more. The lesson of the last crisis was that people hated bailouts for rich people. Rescuing banks, and helping bankers, might not have been so unpopular without the grievous failure even to prosecute those guilty for the behavior that led to the crisis, chronicled in Jesse Eisinger’s brilliant The Chickenshit Club. This time will be different. As one investor asked the Financial Times:

Good question. Then there is the issue of the Fed’s independence, given that the program is backstopped by the Treasury, which is answerable to the president in an election year. This is from Bianco’s Bloomberg Opinion piece when the Fed’s bazooka was first unveiled, but before the junk and muni bond details were announced:

Getting out of this situation, when the program has already shown its ability to boost the stock market, promises to be difficult indeed, and raises the risk of malinvestment on a wide scale. It also faces the risk of creating widespread anger if — as the WSJ argues quite reasonably — the effort to support small businesses is far less successful than this program, which is perceived as aid for people on Wall Street. With hindsight, the post-Lehman bailout can be seen as a Faustian bargain that staved off meltdown and a second Great Depression, but saddled the world with an economy that underperformed for another decade amid mounting political anger and inequality. It looks like that deal is being made again. Bulls can point to what happened to asset prices — and pile into the stock market. Bears can raise the prospects of long-term stagnation and civil unrest, and stay away. Do We Ever Go Back to Restaurants?The second key question is the degree of long-term damage the virus does to the economy. There is still little or no clarity, though the key factors are becoming more clear:

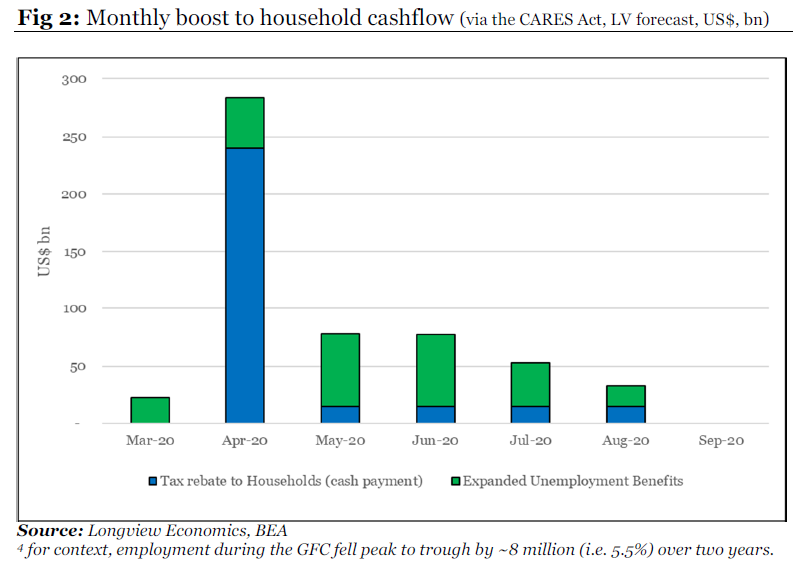

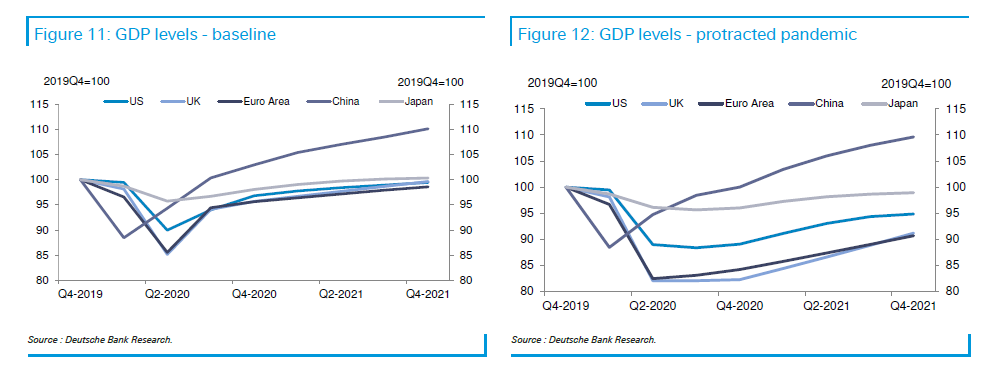

We are all painfully aware of the first question. If the Spanish flu of 1918 is any guide, and it is our only remotely useful historical precedent, then there may be two more waves of lockdowns before we’re done. If tests are available that can prove some have developed immunity, the next shutdowns needn’t be so complete — but there are questions over how soon these can be available, and whether the virus will mutate. Without another lockdown, the pattern identified by the BlackRock Investment Institute should hold. This will be a deeper immediate recession than post-Lehman, followed by a much sharper recovery:  A second and third lockdown, or a first that ends only with a partial return to normal, would change this pattern to something that follows the same trajectory as 2007-08, only with a worse initial hit. With one lockdown and a return to normality thereafter, Longview Economics of London models cash flows to families to show that the much-wanted “V” shaped recovery is possible. This chart looks at the excess cash flows that households would have — a combination of money unspent during the lockdown plus the government’s measures to put extra cash into people’s pockets.  That is a lot of cash available for spending. After this experience, many expect consumers to feel more conservative, so this model assumes an extra 10% saved:  Is this an accurate reflection of likely reality? This chart from BlackRock shows the amount of consumption spending that comes from the service sectors most directly affected by social distancing. Some, like hairdressing, might come back quite quickly. Package holidays and recreation could take much longer. This doesn’t augur well for countries reliant on tourism:  Further total lockdowns or ongoing restrictions will plainly affect this. So will consumer behavior that is still hard to gauge — will people go straight back to old habits, or be more careful and save more? The longer this lockdown lasts, the more people lose jobs and stop spending, and the longer a return to normal economic behavior will take. This is Longview’s model for that outcome, with higher unemployment and a second lockdown:  The less the pickup in cash flows from consumers, the less the likelihood that the economy can roar back. Deutsche Bank AG models GDP levels based on two scenarios — the first on lockdowns that are gradually lifted starting in a matter of weeks, and the second including another lockdown. It acknowledges that even worse scenarios are possible, but it becomes clear that authorities would be well advised to minimize the risk of further shutdowns:  China emerges in the best shape. The other emerging markets, not modeled by Deutsche, would probably be in the worst shape. For investors, there is a decent defense for the rebound in markets, if we can be confident that the lifting of lockdowns likely in the next few weeks will be the end. If not, markets look rather rich. Meanwhile, the importance of changing consumer behavior leads to something else: Possible FuturesI have a request. About a month ago, as North America followed Europe in largely shutting down its economy and asking people to work from home to combat the virus, it became an accepted fact that the experience was going to change us for ever. Whatever the “new normal” is like, post-virus, we seem to be in agreement that it will be different from the old. Plenty of futurology is out there, on broad questions of society and the economy, through to issues of the world of work and technology, and much more. I’m interested in asking readers what you personally think you will be changing, long-term. Will you be happier to work from home, and for children to study from home? Will Americans now be happy to pay the taxes for a national health service? Will Europeans demand changes to their own national health services? And so on. Personally, after a month of forced working from home, going shopping and going to the office both seem much more appealing than they did. But I’d welcome opinions. |

No comments:

Post a Comment