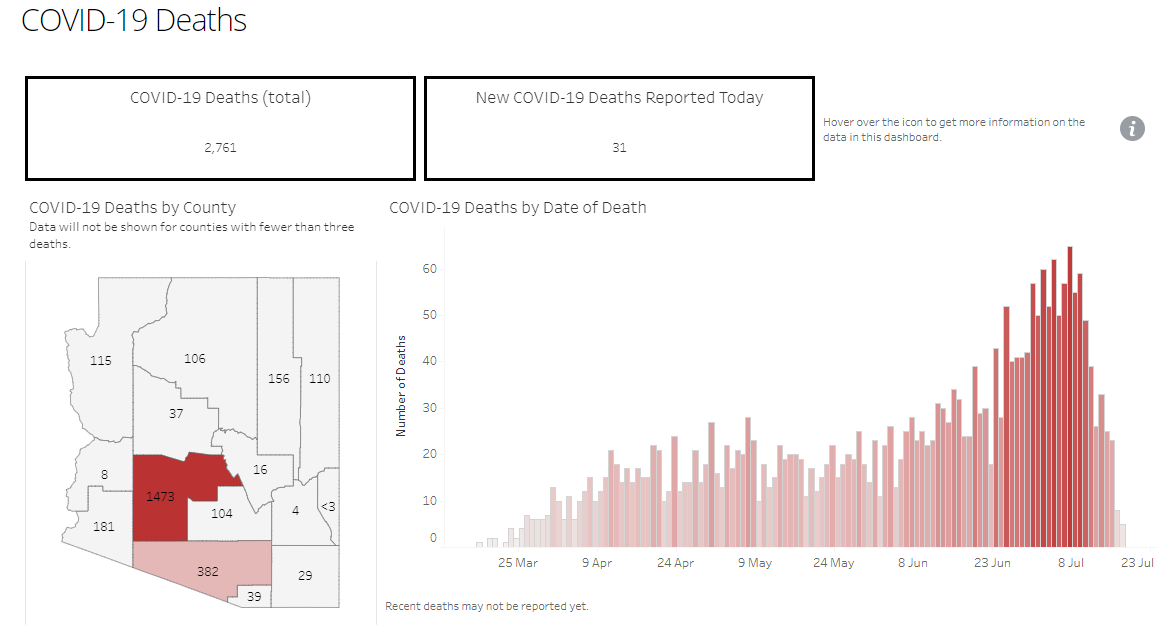

The problem isn’t necessarily whether to issue official stay-at-home orders, or reopen schools, but that a failure to beat the coronavirus has a chilling effect on economic activity. Exhibit a) is the extraordinary difference in the return to restaurants in Germany (which appears to have the virus relatively under control) and the U.S. (which does not). This chart is from George Saravelos of Deutsche Bank AG:  America isn’t going to reopen much more until the populace is convinced that the pandemic is under control. And the differences over fiscal policy currently roiling Congress could be critical because the number of people still on some form of assistance (normal jobless claims or the specific Covid relief introduced earlier this year) remains very high. This chart from High Frequency Economics illustrates the situation clearly:  It therefore grows vital to bring the R number — the number of new people who each infected individual will infect on average — below the level of 1. Once this has been reached, the disease is no longer spreading. Unfortunately, Davies writes in the Financial Times, R is above 1 in 45 of the 50 U.S. states, which between them account for 95% of U.S. GDP. Unless this number reduces quickly, the likelihood is that the disease will become prevalent enough to change people’s behavior, whatever politicians do. But if we look across the Sun Belt states where the disease is rampant, the data give at least some cautious signs for optimism. The surge in cases looks as though it should pass without overwhelming hospital systems — although there is no reason for complacency. For evidence, I return toArizona’s Covid dashboard, which includes lots of useful information that nevertheless has caused much confusion. The state has suffered a serious bout of the pandemic, but the rate at which it puts pressure on hospitals seems to be leveling out. This is the number of confirmed or suspected Covid-19 inpatients in Arizona hospitals:  We see a similar leveling off in the total number of Covid patients in intensive care:  This has left total use of intensive care beds (including by non-Covid patients) at levels that the state’s hospital system can just about sustain. This is the percentage of ICU beds in use:  Had the wave of hospitalizations continued to rise for another a week, these charts suggest that ICUs would indeed have been overwhelmed. It looks, at this point, as though this can be avoided. This leads, however, to the most important question of all, which is the death rate. This is what economists would call a lagging indicator — generally death only occurs after people have been infected, had symptoms, and been hospitalized. The legal process ensures that many deaths don’t show up in the statistics for a week or so — so it is best to ignore the most recent data in the following chart, which shows deaths from Covid in the state:  To ram home that the apparent decline in the numbers of the last week is merely an artifact of the way deaths are reported, look at this screenshot of the same chart taken about five weeks ago, on June 16:  We now know that deaths were in fact rising significantly at the point that this chart was published. So far, according to the official tally, 2,761 Arizonans have died of the pandemic, of whom 27% are aged 64 or less. Can the death rate also hit a level in the next week, as hospitalizations appear to have done, and then start to decline? This is naturally the most important human question. But the chances of returning economic activity and avoiding a double-dip recession could also depend on physicians’ attempts to keep people across the Sun Belt alive in the next few weeks, as well as on the ability to everyone to change their behavior in the way that is needed to bring R below 0. The EU’s Lost WeekendThe European Union stripped of the U.K. is a different body. Without the British to behave badly, put up obstructions and provide a convenient scapegoat, all kinds of previously unnoticed fault lines are being revealed. And the precedent of Brexit has prompted even more brinkmanship than usual at the Special European Council summit. Originally timetabled to take place Friday and Saturday, it went on into Sunday, where it was still unfinished at the time of writing (approaching midnight in New York, and 6 a.m. Monday morning in Brussels). Instead, a fourth day has been announced. This is the kind of torture that the British used to inflict. How bad is the damage to the EU? And what effect should it have on the investment world? The aim of the summit, the first since the pandemic hit, was to thrash out a post-Covid recovery fund. This had dual significance. Most importantly, the idea is that the EU will borrow in common, and then disburse the money where it is most needed. It is at least the beginning of a truly common fiscal policy, to join the common monetary policy that members of the euro zone have had since adoption of the single currency in 1999. Secondly, and in the shorter run, it could ram home the notion that the EU is far more functional than many believed, and that it could organize a better response to Covid-19 than the U.S. The European public health response has been much more effective; now to try to buttress the economies most harmed by the pandemic, led by Italy. All of this agenda was known, and borne on a tide of increasing optimism as the summit approached. However, the baseline entering the weekend was that a deal was unlikely. That helps to explain relatively calm trading in Asian hours Monday morning, as traders arrived to discover there was still no clear conclusion, positive or negative. The euro oscillated within its prior range of between $1.14 and $1.145. Nobody could tell from currency action that anything significant had happened. So it doesn’t look as though success had been written in to the foreign exchange markets:  Looking deeper, any move toward a common fiscal policy would make the currency far more resilient against shocks. Despite this, and other factors moving strongly in the euro’s favor (such as success in containing Covid, and narrowing interest-rate differentials with the dollar), it is still some 9% weaker against the U.S. currency than at its recent peak in early 2018. It doesn’t look as though much success in building a recovery fund has been priced in. On that basis, it is possible that EU leaders’ success in finding something to keep discussing will be a market positive. If they can nail a deal, after a nasty and fractious weekend, it will be a big positive. Optimists can say that the leaders wouldn’t have consented to hang around into Monday unless a deal were close. Those are the reasons for optimism. On balance, they probably outweigh the reasons for pessimism, of which there are still plenty. The battle lines are over how much should be in the fund, how much should be given as grants and how much as loans, and whether individual countries should have the right of veto over grants to other countries. There is a separate line of conflict over whether respect for the rule of law can be used as a criterion for approving grants or loans. These divisions cut to the heart of the federalist dilemma; how far to go on the journey from a collection of independent nations to an overall federalist state? With Britain now absent, those blocking the way are the so-called “Frugal Four,” of the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden. The French and Germans, having previously been very tough on the countries of the Mediterranean, have switched roles and are now the “nice guys,” championing grants. The Netherlands, an EU founder member, is traditionally deeply committed to the European project. Thus it is a big deal for President Macron to say the Dutch are behaving like the British (a serious insult), for Portugal’s prime minister to suggest they leave, and Italy’s prime minister to accuse them of blackmail. There have also been many pointed references to Dutch corporate taxation, which others in the bloc regard as a way for multinationals to avoid paying taxes in the EU. Separately, the inability of the rest of the EU to bring Hungary and Poland to heel over what are seen as increasingly authoritarian moves is another problem. With the British gone, there was a belief that France and Germany, acting together, would be able to pull smaller countries to heel. That hasn’t happened yet. A group of small countries, whose joint population is smaller than the U.K.’s, have made themselves just as difficult as Margaret Thatcher ever did. The actual details of the fund barely matter. What matters is whether the EU reconciles the differences enough to edge forward, just as it has managed to do for seven decades. The odds are that it will. But the depth of divisions that have been revealed will tamp any great excitement. Progress will be slow. We might expect something similar for the euro. Survival TipsThis is a tip that comes with a deadline. Each week for some months now, Britain’s National Theatre has been streaming for free a filmed version of one of its more famous staged productions. This week’s offering is an extraordinary performance of Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus, now best known for Milos Forman’s 1984 Oscar-winning film. You have until 7 p.m., British time on Thursday, July 23, to watch it. If you’ve seen the movie, it’s still very much worth seeing a production with live musicians on stage, and a significantly different ending. Shaffer rewrote the play when he produced the movie screenplay. For the uninitiated, the play is based on the true story of the composer Antonio Salieri, who said repeatedly on his death bed that he had killed Mozart. Amadeus is an imagined account, as told by Salieri, of how he might indeed have gone about causing the death of Mozart (who is portrayed — again with some historical accuracy — as an obnoxious young twerp). You also get to listen to lots of great music by Mozart: This is the serenade that alerts Salieri to Mozart’s genius; this is the solo for The Marriage of Figaro that Mozart builds out of Salieri’s welcome march for him; this is one of the arias from The Magic Flute which Mozart’s friends in the freemasons took to be poking fun at them; and this is Tuba Mirum from the Requiem on which Mozart was working at his death. To find out what role Salieri might have played in the writing of the Requiem, watch the play. It’s really something else, and worth devoting one of the next three nights to it. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

| Before it’s here, it’s on the Bloomberg Terminal. Find out more about how the Terminal delivers information and analysis that financial professionals can’t find anywhere else. Learn more. |

| You received this message because you are subscribed to Bloomberg's Points of Return newsletter. |

| Unsubscribe | Bloomberg.com | Contact Us |

| Bloomberg L.P. 731 Lexington, New York, NY, 10022 |

No comments:

Post a Comment